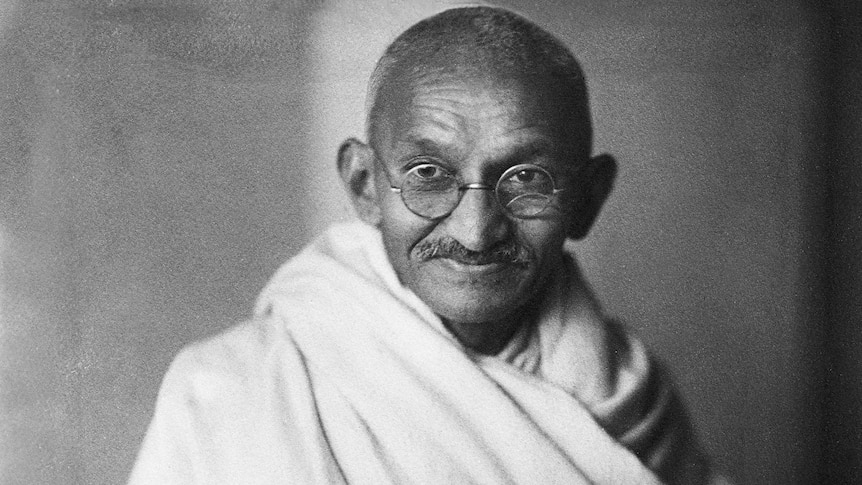

On the 150th anniversary of his birth – October 2, 2019

The first scene in Richard Attenborough’s movie, Gandhi, is the assassination of the protagonist by a Hindu patriot who feared that the Mahatma’s emphasis on non-violence would prevent newly independent India from pursuing its national interest with military vigor.

At the time, January, 1948, Gandhi’s life seemed to have been a spectacular failure. His beloved India had been partitioned into Hindu and Muslim majority states accompanied by devastating fratricide resulting first in the uprooting and deaths of millions of people along religious lines, and secondly the beginning of a tension that was to cause numerous wars that in turn launched a debilitating arms race. India had achieved independence from the imperial rule of the British Raj but not from modern industrial society as introduced by western imperialism; even Gandhi’s disciple, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, believed in rapid industrialization and urbanization in an attempt to transform a billion people into consumers.

Gandhi was born on a sub-continent that was predisposed to the West, both intellectually and materialistically. Europeans, backed by gun boat diplomacy, had flooded the local markets with their manufactured products, exported millions of Indian workers to far-off colonies, and, convinced of their moral superiority, imposed profound social and cultural reforms on their subjects. Many Indians were forced to abandon their immemorial villages with a life defined by religion, family and tradition, for a society dominated by white men who were driven by the profit motive and sustained by a belief in the national state enforced by superior weaponry.

Initially Gandhi bought into this scenario. He received a western-style education, studied law in London and, on his return to India, set up a law practice, as part of which he was sent to South Africa in 1893 by an Indian trading firm. In what was to be a 21 year incubation period, Gandhi was subject to a number of racial humiliations and witnessed the moral and psychological vacuum of a country in which, as in India, the old ways and life styles were being replaced by the cultural and political norms of western capitalism. And as a stretcher bearer during the Boer War he experienced first hand the violence of early twentieth century warfare.

He was not alone in his awakening. Many Chinese and Muslim intellectuals argued that the ideals of the European Enlightenment were no more than a moral cover for racial hierarchies; they sought comfort in a revamped Confucianism and Islam, only later to be pushed aside by hard-line communists and fundamentalists. Gandhi’s difference was the realization that rampant nationalism or religiosity would simply replace one set of deluded rulers with another – “English rule without the Englishman,” he called it – and his term satyagraha, literally holding fast to truth in Sanskrit,argued for political and cultural reform by non-violent means. It was truth as moral engagement.

To Gandhi, the industrial revolution, by turning human labor into a source of power, profit and capital, had made economic prosperity the goal of politics, rather than religion, ethics and the well being of all. The traditional virtues of India – simplicity, patience, frugality, otherworldliness – were denigrated as backward. Thus Gandhi dressed simply and rejected all outward signs of being an intellectual, even though his Collected Works cover over 100 volumes. In South Africa his closest friends were English and German Jewish intellectuals; he was initiated into Hindu philosophy by a Russian and he quoted as often from the New Testament, Ruskin, Thoreau, G.K. Chesterton and Tolstoy as from the Bhagavad Gita. Rather than present himself as a national politician, which he was, he focused on moral self-knowledge and spiritual strength, upholding the self-sufficient rural community over the nation-state, cottage industries over factories and manual labor over machines.

The traditional authorities fought back, perhaps with the fear that can come from deep truths about which they were in denial. Winston Churchill, who regarded himself as a true democrat, said in 1930, “It is alarming and also nauseating to see Mr. Gandhi, a seditious middle temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well known in the east, striding half-naked up the steps of the viceregal palace, while he is still organizing and conducting a defiant campaign of civil disobedience, to parley on equal terms with the representative of the king-emperor.”

In more ways than one, Gandhi, in his belief in self-determination for all people and the universal equality of all of mankind, was much the greater of the two democrats. It is no surprise that Churchill loathed Gandhi. Gandhi loathed no one.

By the beginning of 1948, in the midst of civil war and Indian capitalism, the 80 year old Gandhi may well have been discouraged. Shortly before his assassination he had embarked on yet another hunger strike but had vehemently refused all police protection; it was almost as if he welcomed an end to a life-long struggle that seemed not to have produced any tangible results.

And yet his name is wistfully invoked in many conflict zones today, not least by the non-violent demonstrators who prayed unflinchingly on Kasr al-Nil, in Cairo, as they were assaulted by Hosni Mubarak’s water canons, or in the yearning for a person of his stature in either Israel or Palestine, if not both. He inspired many globally revered figures, including Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and Aung San Suu Kyi (before the Rohingya debacle.)

Besides Indians, who were motivated to something like self-sacrifice in the name of the common good, Gandhi’s message resonated with that part of the British soul that was empathetic to the values he embodied. It worked too in Alabama and Mississippi in the 1950’s and 60’s, whereas it did not work with Stalin or Mao, nor would it have done with say the Khmer Rouge. Indeed Gandhi’s suggestion in the 1930’s that Jews should resist the Nazi’s with non-violence was woefully misgided.

As the spiritually minded, sage-like thinkers, advocating ethical responsibilities and duties, have faded from the mainstream of our society, so hard they been replaced by ideologies, institutions, science and commerce. The writing is still there – Simone Weil, Reinhold Niebhur, Czeslaw Milosz, Vaclac Havel – but it is hardly at the forefront of the national debate. When it comes to the challenge of trying to live ethically in the midst of radical change, of trying to be moral men and women in complex, immoral societies, Gandhi still seems to be the most distinguished figure in this countercultural tradition. “He was the last political leader in the world who was a person, not a mask; the last leader on a human scale,” Dwight Macdonald wrote in a tribute after his assassination.

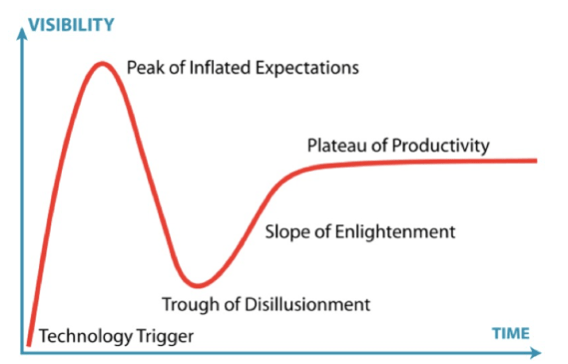

How, you ask, do honey bees relate to this story? First, in northern climes it is easy to feel disillusioned when spring reveals a number of dead-outs in the apiary. Despite all our caring, all our work, all the money we spent on nucs and packages and queens and sugar and medications and treatments, there may be no tangible results of our effort, of our caring. The survivors struggle in an environment increasingly despoiled by the artifacts of agri-chemical businesses which are driven by profit rather than by morality, ethics and self-knowledge. Most of us are hobbyists, members of a cottage industry, using manual labour rather than machines, and proudly so. We can feel helpless when the bees fly beyond our immediate reach and venture unknowingly into a toxic realm. The Mahatama might have used a hive as a symbol, rather than a spinning wheel.

Gandhi’s great gift was to bring together in public spaces masses of highly motivated and disciplined protesters with a common passion. As beekeepers we are not alone in our loss; indeed, like the honey bee, we cannot survive in isolation. And the bees, our wards as well as our teachers, are not only motivated and disciplined but also demonstrate the traditional values that Gandhi so admired, not least, simplicity, patience and frugality. They are beacons of hope in the best of countercultural traditions.

Secondly, Gandhi’s ecological world view, summed up in his homily “Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s need but not for every man’s greed,” supports the increasing move towards backyard beekeeping, organic farming, farm-to-table restaurants and sustainable lifestyles – the kinds of practices that were common before the steam engine and the factory, a time when the majority were stewards of the land even if few could afford meat – “To bring home the bacon” originated in the late Middle Ages as a sign of unusual good fortune.

And thirdly, Gandhi realized that the triumph of the scientific world over the ethical one has desacralized nature and made it prey to ruthless, systematic, extractive economies who measure only in terms of the bottom line – mountain top mining, deforestation of the Amazon basin, monocultures covering the mid-west, factory hens, hormone induced beef production, ‘clean coal,’ fracking, unrestricted off-shore drilling, to name a few. Just as happened in nineteenth century India, we misguidedly struggle to achieve our independence from total reliance on nature and circumstance, but not from the dictates and materialism of a post-industrial culture.

It is easy to romanticize Gandhi as he set out not only to undermine the system but also to change the hearts and minds of his opponents; in effect, to humanize them. He was not perfect but he attracted respect with his sheer perseverance in the face of overwhelming obstacles, what has been labeled his ‘moral stubbornness.’ He made it clear he was in it for the long haul, as are we, the beekeepers, as we fight for environmental justice and reform.

David Lean’s 1962 movie, Lawrence of Arabia, also opens with the death of the protagonist – a motorcycle accident in 1935 in Dorsett, England. After the First World War General Edmund Allenby, who had been Lawrence’s commanding officer, described him as “the mainspring of the Arab movement,” and as with India, the nationalism he inspired has not met with significant peace in the Middle East. Nor is Lawrence’s name spoken of with the same esteem as his contemporary, Gandhi, despite his many monumental acts of bravery, in part because Seven Pillars of Wisdom does not have the moral underpinning of the Mahatma’s writings, and in part because neither Lawrence, nor very few others, could replicate the fierce, transparent, internal battle that Gandhi fought with himself, an endless inner struggle between him and his idealized image of himself, that resonated with so strongly with what others saw and experienced. Thus is he called Mahatama, or Great Soul.

Honey bees, their health and rates of attrition, are both a touchstone and a reminder of what happens when we as a society forget the difference between control over nature and living with nature. The bees, the soul of nature, have not forgotten and they rely on us, the humble beekeepers, to relay their message. We can never go back to a pre-industrial age but we can strive for a balance. Honey bees offer a bridge, a connection, a link between the best of the old and the finest of the new.