An estimated 50% of new beekeepers discontinue within their first year and a further 25% within the next two years. Many suggestions have been proffered to reduce this attrition, including mentoring programs and more beginner courses, and yet I wonder if there is something more involved.

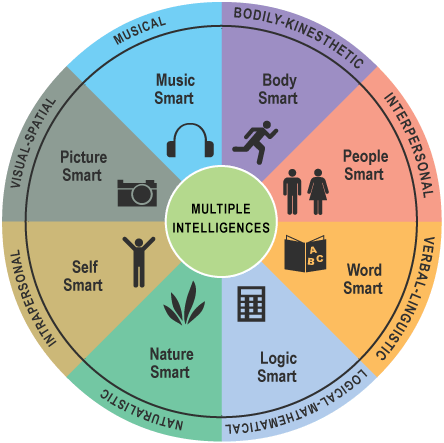

We all begin this wonderful pursuit for a variety of reasons, each of them valid, and most who choose not to continue do so in the spring, disillusioned by the loss of the colony or the stress of over-wintering. Discussions with disenchanted nu-bees suggest a pattern related to Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Gardner postulates that not only do we have different ways of learning and processing information but these methods are relatively independent of one another, leading to multiple intelligences as opposed to one general intelligence factor, traditionally expressed as IQ, or Intelligence Quotient.

Traditionally we measure intelligence very narrowly and label people accordingly. The limitations of ‘verbal and non-verbal’ intelligence were brought home to me some fifteen years ago by a non-traditional student in a college class. ‘Joe’ was in his early 30’s and had been advised by his high school that he was not college material because he did not write easily and was not good at mathematics. He sat in the front of the class, asked if he could record each lesson, and arrived each morning armed with some perceptive and penetrating questions, the like of which I was not used to receiving. Joe was an audio learner, and as he listened several times to each class after he returned home, these questions would emerge.

I discovered eventually that Joe is a superb guitarist who composes, plays and teaches jazz guitar. This is a man with superb musical intelligence which had not been recognized at high school. He discovered and nurtured them by himself, and coming back to college with it’s more traditional emphases was an immense act of courage. I guess we all know stories like this – people who have succeeded in life despite poor performances at school. We also know those, sadly, who have never recovered from being labeled at school as ‘failures.’

Howard Gardiner has to date identified nine possible modes of intelligence and believes there are many others. We all have them with one or two being more dominant.

The first three are the bases of traditional intelligence testing. Logical-mathematical intelligence has to do with numbers and reasoning and is expressed in recognizing abstract patterns, scientific thinking and investigation and the ability to perform complex calculations. Linguistic intelligence involves words, spoken or written, and is seen in those who learn best by reading, taking notes, listening to lectures, and by discussing and debating about what they have learned, whereas spatial intelligence is the ability to visualize with the mind’s eye. Artists, designers and architects come to mind, as do those with a love for jig-saw puzzles.

The core elements of bodily kinesthetic intelligence are control of one’s physical motions and the capacity to handle objects skillfully. Such people learn better by hands on, practical applications and are generally good at physical activities such as sports or dance.

Musical intelligence has to do with sensitivity to sounds, rhythms and tones, whereas Interpersonal intelligence is one’s empathy with others, in particular a sensitivity to others’ moods, feelings, temperaments and motivations, and the ability to cooperate in order to work as part of a group. Helen Lang, for example, from Baltimore, had no more than a third grade education yet she was a much-loved wise woman who seldom left a grocery store without gently enquiring after the well being, if not the life history, of the lady at the register. Apparently, before Mary and I were married, she expressed her approval of me by observing that “He has his soul on straight.”

Intrapersonal intelligence, by comparison with interpersonal, reflects one’s introspective and self-reflective capacities. This refers to having a deep understanding of the self and is conveyed in philosophical and critical thinking.

Some proponents of multiple intelligence theory proposed spiritual or religious intelligence as a possible additional type. Gardner suggested instead the term existential intelligence, ie. the ability to contemplate phenomena or questions beyond sensory data, such as the infinite and infinitesimal.

Which brings us to naturalistic intelligence, or the nurturing and relating of information to one’s natural surroundings, such as by gardening and farming, and of course keeping honey bees. Naturalistic intelligence can be observed as much as it can be measured. Larry Connors has described how, when he first introduces new beekeepers to a working hive, some lean in and others lean away. It is the former, he suggests, who will succeed long term. The intimation is that this latter group has a dominant naturalistic intelligence which is unfailingly curious to anything involving the natural world. When people come to visit Mary and I, most walk into the house and settle around the kitchen table. There are a few, a distinct minority, who insist on going outside, walking around the garden, even asking if they can see the hives. Only then can they relax and come inside. They have a naturalistic intelligence that needs to be satisfied.

Schools focus primarily on linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligence and as a culture we esteem those who are highly articulate or logical. Dr. Gardner maintains that we need to give equal recognition to those who show gifts in the other intelligences: the artists, architects, musicians, naturalists, designers, dancers, therapists and entrepreneurs who enrich our world. Unfortunately, many children who have these gifts do not receive much validation in school and, when their ways of thinking and learning are not addressed in a linguistic or logical-mathematical classroom, are labeled “learning disabled”.

Is this perhaps why so few children appear to be interested in beekeeping, that they do not feel it is acknowledged or rewarded in schools as important? Certainly several attempts to place observation hives in the science rooms of local schools have not been successful whereas several families who have installed a honey bee colony have made it an integral part of their home school program, wherein the curriculum is broader and more individualized than that of most public schools. I think in particular of one family who, studying Russia when the bees arrived, invited the three children to name the queens after different Czarinas and to research both the historical and apian rulers.

It might also explain why many people come to beekeeping at a time in life when they realized for themselves their specific interests and talents, as well as what brings joy and fulfillment to their lives, especially when that enjoyment comes outside of the mainstream of ’normal’ life styles.

My guess is that we can each see in ourselves combinations of these nine traits. I have various degrees of linguistic, bodily kinesthetic, intrapersonal, existential and naturalistic intelligences, but poor logical-mathematical, interpersonal and spatial intelligences, and Van Gogh’s ear for music. Try as I might I cannot learn a musical instrument, cannot read music, and if given the choice, would rather listen to a talk show on the car radio, no matter how bad, than a musical program, no matter how good. For a long time I blamed myself as somehow incompetent; now I accept that it’s the way I am wired, and I focus on what I can do rather than bemoan what I cannot. Thus I’m OK with the fact that I would rather send e-mails than make telephone calls, and if it has to be the latter, to keep them as short as possible. Mary is the exact opposite, and the monthly statements of our respective cell phones reflect it.

I have used previously the image of an expanding jigsaw puzzle with an apparently limitless number of pieces that will never quite come together completely. Glimpsing the bigger picture is a challenge to, and a reward for, my specific combination of traits; it brings joy, which in turn stimulates motivation and perseverance. In the equation promoted by Harrison Owen, the creator of Open Space Technology, motivation = passion + responsibility.

The frustrations of those wannabees who decide not to continue with keeping bees are understandable. Like me with the piano and guitar, they began with the best of intentions, they dearly want it to work, but what to others are challenges that lead to a sense of achievement are to them obstacles that prove frustrating and debilitating, and beekeeping becomes a trial to be endured rather than a source of constant delight. I keep leaning in, and respect those who need to pull away.