In January I was forwarded an article from the March, 2023 edition of Science Robotics titled A Robotic Honeycomb for Interaction with a Honeybee Colony, by Rafael Barmark et al. Using the language of the report, it described ‘a robotic system designed to observe and modulate the winter bee cluster using an array of thermal sensors and actuators . The robotic system was able to observe the colony by continuously collecting spatiotemporal thermal profiles of the winter cluster, to modulate the bees’ response to dynamic thermal stimulation, and, after identifying the thermal collapse of a colony, to create a “life-support” mode via its thermal actuators.’

In layman’s language, these sensors, embedded in the comb, not only measure and observe the movement of the winter cluster but, in the case of a weak colony, can be activated to modulate the temperature in the cells, supposedly to augment their survival.

This is the culmination, but not the endpoint, of what Randy Oliver calls the 4th Agricultural Revolution. The first was the invention of agriculture some 12 000 years ago, followed by its industrialization starting in the late 18th century and culminating in the use of the internal combustion engine in the form of tractors and trucks. The third is what Randy calls the Green Revolution, which in my estimation started when the Soviets successfully launched a manned space rocket, Sputnik. Besides emphasizing math and science in schools (often at the cost of art and music) American farmers were encouraged to ‘farm fencerow to fencerow,’ so that the US would be agriculturally self-sufficient; this meant, among other things, that the hedgerows, so vital to birds, insects, animals and wild flowers, were plowed under. Perhaps the best known aspect of the Green Revolution was the production of high yield crops, especially rice and corn, not least in India, but with it came some significant downsides – a population explosion, heavy use of synthetic fertilizers, cheap labor, heavy use of water and increased use of pesticides, not to mention increased costs which affected many small farmers dearly – and which I described at length in a previous column.

The fourth revolution introduced electronic technology in which Randy includes the internet, Artificial Intelligence, biotechnology, gene editing, robotic labor, precision dispensing of chemicals, vertical farming and alternative energy sources.

And we cannot expect honey bees to be unaffected by this process.

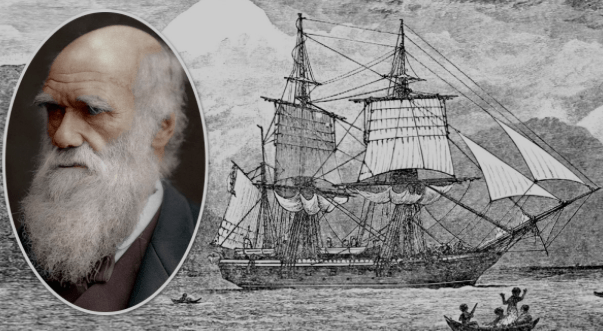

On the same day I received the article from Science Robotics, I read Anne Murphy Paul’s description of Charles Darwin’s famous voyage starting in 1831. The 22 year old, torn between following a career as a doctor, a parson, or one that allowed for his burgeoning interest in natural history, received a letter from his former tutor at Cambridge University informing him of a position as a naturalist on a two year expedition aboard the HMS Beagle.

He had never kept a journal before but began to do so under the influence of the experienced ship’s captain, Robert FitzRoy, whose naval training had taught him to keep a precise record of everything happening aboard the ship and of every detail of the ocean-going environment. Each day the two men ate lunch together, after which FitzRoy wrote up both the ship’s log and his personal journal. Darwin followed suite : his field notebooks, his scientific journal and his personal diary were updated daily as the two years of the expedition turned into almost five.

Recording such data requires close observation of one’s surroundings, the ability to run through a mental checklist of features that might be recorded, and the skill to organize them clearly. In addition, the process of taking notes in the field requires us to select, discriminate and evaluate (ie. higher order thinking skills) which in turn lead to deeper observation.

Beekeeping technology is rapidly becoming more copious and more intrusive, yet each of us has access to pen and paper. When asked, most beekeepers acknowledge the importance of keeping good notes, and yet only a minority actually do so. It’s like checking for varroa – we know the importance of monthly mite checks, yet only a few do it. And taking notes is the first step; what is critical is using that recorded data to make decisions for the benefit of the bees as well as for one’s own professional awareness and development.

HMS Beagle returned to Plymouth Sound on October 2, 1836. Darwin spent the next three years processing those boxes of note books and another twenty years discussing and refining his conclusions, until the eventual publication of The Origin of the Species in November, 1859.

With the plethora of technology available today, it is easy to forget that a pencil and a notebook in the hands of a young Charles Darwin were key to developing a theory that would change our perception of the world, even as it did not seem so at the time.