in January Mary and I found ourselves in St. Petersburg, Florida. With uncharacteristically cold, wet and windy weather we decided to take advantage of some of the remarkable museums in the city, starting with the one devoted to the works of the surrealist painter, Salvador Dali, which contains the largest number of his works of any museum outside of Spain.

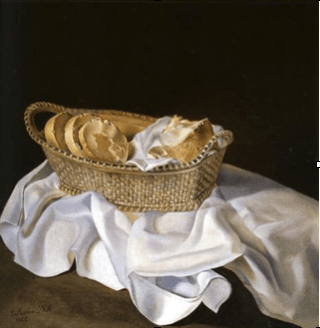

There were two pieces, diametrically opposed in style and purpose, that caught my eye. In 1926, when he was 22 years old, Dali was required to submit a piece to the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, the predominant art school in Madrid, to prove that he had the artistic skills worth of being accepted. The result was a relatively small piece he titled “The Basket of Bread.” It is a technical masterpiece; clearly, at a young age, he was already a master of his craft. And I guess he knew it. As part of his final exams he was required to meet with some of his professors to discuss the Renaissance maestro, Raphael. He refused such a meeting on the grounds that, in his opinion, he knew more about Raphael than they did! He was evicted from the Academy without ever completing those final exams.

In 1939, when he was 35 years old, after experiencing the horrors of the Spanish Civil War and with his country again under siege, this time from Nazi Germany, Salvador and his wife Gala, moved first to France and then to the United States via Portugal, where he was to spend the next eight years, dividing his time between New York and the Monterey Peninsula, California.

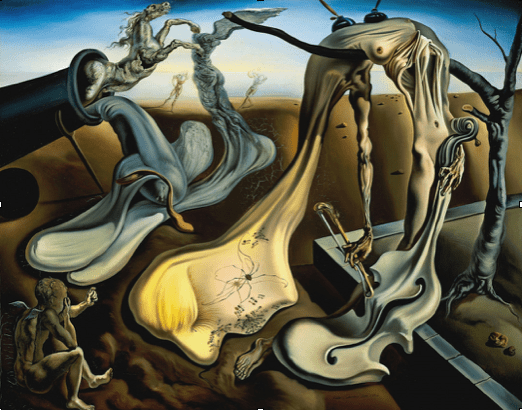

His first painting completed on American soil was titled “Daddy Longlegs of the Evening – Hope.” The title is a reference to a French legend to the effect that the sighting of a daddy long legs in the evening is a good omen.

It is a grotesque scene with haunting, unsettling, imagery. In the lower left corner a winged child, possibly an angel, shields his eyes as he points to the unfolding horrors. A canon shoots an eyeless, purifying horse, while a soft airplane oozes to the ground. A sculpture of Nike, the Greek Winged Goddess of Victory, headless, rises in bandages from the deflated plane. The gratuitous figure in the center, eviserated and draped over a leafless, withered tree (the destruction of the feminine side that is endemic to all wars?) holds a soft cello that is no longer capable of making music; inkwells sprout from the body, suggesting the eventual treaties that will resolve the crisis; after all the pen is more powerful than the sword. A daddy long legs appears on the face, hence the hope amidst the chaos and destruction – witness the wasteland in the background with two humans reduced to tendrils of smoke. The essence of humanity is vulnerable amid the carnage.

This painting occupies the same rarified area as Picasso’s “Guernica” which also was a response to the horrors of the Spanish Civil War three years earlier. Both are in a league of their own in terms of anti-war statements; there is no explicit violence, no bloodshed, no gore, in either, yet each is a powerful statement of the ruinous, destructive nature of war. Unlike Picasso, Dali included a semblance of hope.

Incidentally, one of the docents at the Dali Museum asked her group how long the average museum visitor spends in front of an art work in a museum. The answer – five seconds, and that includes reading the label!

But that is not what struck me about these two paintings.

In the mid-1990’s the power point program became available to school students as a means of presenting their projects. The first, and overwhelming, response, was, and often still is, to spend the majority of the preparatory time and effort on the visual appearance, with very little time spent on the content, not realizing that that this is the old issue of image v substance, that even the most beautiful presentation is ineffective without a solid core.

At the age of 22, Dali was a highly competent artist in the accepted sense. And it was this base which allowed him to become a highly competent artist in a non-conventional, initially disputed, style called surrealism. Time and work spent on the basics is never time wasted; indeed it is essential to further growth. It is the biblical story of a house built on sand … Similarly good educators teach an estimated 10 per cent of what they know. The remaining 90 percent is not wasted; it is termed ‘reserve power’ and is there in case one needs it.

Some 15 years ago, at Buckfast Abbey in Devon, England, Claire Densley told me that she strongly advises her new beekeeping students not to do anything for the first five years after the class except master the basics. She wants them to become absolutely proficient in handling, reading and intervening in a colony, to have a foundation of stone, to have the reserve power when needed as they later start to experiment, to branch into specialist fields, to try something a little different. It was advice that came vividly to mind in the Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida.