Lars Chittka’s Mind of a Bee, and Stephen Buchmann’s What a Bee Knows: Exploring the Thoughts, Memories and Personalities of Bees”, examine the question of sentience in plants and animals, an issue made more complex by the challenge of understanding minds that process information in ways profoundly different from our own, as described by Ed Yong in An Immense World. Perhaps the critical question was posed two hundred years ago by Jeremy Bentham: “The question is not can they reason. Nor can they talk. But can they suffer?”

In place of a nervous system, plants have a chemical pathway in the form of glutamate, a neurotransmitter at the point of leaf separation. Furthermore, plants having their leaves nibbled on by a herbivore can release volatile organic compounds through interconnected root systems to the point that nearby plants release antifeedant molecules, thus making their own leaves unappealing to the herbivore, thereby preventing over-feeding in any one area. In her remarkable book, Wildscape, Nancy Lawson describes on the one hand how, in Iran, marigolds and salvias growing next to a busy highway had elevated levels of stress hormones, and on the other hand, in Israel, a species of primrose as able to increase the sweetness of its nectar in the presence of bees’ wingbeats.

Clearly plants physiologically can distinguish between stimuli, but whether this sensation is pain or pleasure as we understand it remains an open question.

Many animals, including us, are vertebrates with similar nervous systems and the capacity to remember, the latter quality often termed instinct because we do not have the ability to probe the emotional state of these sentient beings. Lars Chittka, a professor in sensory and behavioral ecology at Queen Mary University of London, argues that bees have remarkable cognitive abilities which not only make them profoundly smart with distinct personalities, but allow them to recognize flowers and human faces, exhibit basic emotions, count, use simple tools, solve problems, and learn by observing others. They may even possess consciousness.

What made the headlines was Chittka’s experiment to determine if bees could learn to avoid predators purely as an adaptive response. The experiment employed a robotic crab spider that lurked in flowers, briefly grabbing a bee and then releasing it unharmed. After that negative experience, the bees learned to scan the laboratory’s flowers to make sure they were spider-free before landing. But much to Chittka’s surprise, some bees also seemed to exhibit what he describes as a kind of post-traumatic stress disorder. “The bees not only showed predator avoidance but they also showed false alarm behavior,” he wrote. “After scanning a perfectly safe flower, they rejected it and flew away, seeing a threat where there was none.”

Buchmann and Chittka also argue for bees’ self-awareness and emotions, including their ability to suffer, meeting Jeremy Bentham’s minimum parameter for sentience. This could have significant implications for agriculture. Previous research has focused on the role of bees in crop pollination, but the work being pioneered by Chittka’s colleague, Stephen Buchmann, currently an adjunct professor in the Entomology and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology departments at the University of Arizona in Tucson, could force an ethical reckoning with how honey bees are treated.

In the US, commercially managed bees are considered livestock by the Department of Agriculture and are treated as a workhorse for food production, just as cattle in feedlots serve the beef industry. Because a bee’s brain is so tiny the assumption was that there could not be much going on in something so small and with so few neurons. Insects were considered to be semi-robotic, with no capacity to feel pain or to experience suffering. Instead, writes Buchmann, “Bees are self-aware, they’re sentient, and they possibly have a primitive form of consciousness.” This raises practical and existential quandaries. Can large-scale agriculture practices continue without causing bees to suffer, and is the dominant western culture even capable of accepting that the tiniest of creatures have feelings, too? “We are blasting bees with huge amounts of agri-chemicals and destroying their natural foraging habitats,” says Buchmann. “Once people accept that bees are sentient and can suffer, I think attitudes will change.”

it is only in the last decade that research technology has become sophisticated enough to analyze the neurobiology of the bee brain. Two examples. A recent study (May, 2023) at the University of Sheffield in Yorkshire, England, was designed to discover how honey bees excel at quick decision-making. They are the only pollinators that must get enough food for themselves as well as harvest large amounts of pollen and nectar to support their colony, which means memorizing the landscape, evaluating flower options and making quick decisions in a constantly changing environment. Chittka likens it to shopping in a grocery store, where you are rushing up and down aisles comparing products for the best deals and keeping a mental account before you return to the product you ultimately decide to buy.

The task of the Sheffield group was to study how this might apply to improving artificial intelligence systems and devices – the aim was to ‘develop skilled machines that can think like bees,’ according the the study leader, Dr MaBouDi. 20 bees were trained to recognize five different colored flowers – blue flowers contained sugar syrup, green flowers contained bitter tonic water and the remaining colors sometimes had glucose. The bees were then released into a custom-built garden where flowers contained only distilled water to see how they performed.

The experiment found they made a bee-line for flowers they thought would have food – landing there in an average of 0.6 seconds, which is faster than another other animal – and were just as quick to avoid flowers they thought would not have food. Next, MaBouDi et al. developed a computational model which could faithfully replicate the pattern of decisions exhibited by the bees, while also being plausible biologically. This approach offered insights into how a small brain could execute such complex choices ‘in the moment’, and the type of neural circuits that would be required. “What we’ve done in this study is reveal the underlying mechanisms which drive these remarkable decision-making capabilities. We can now use these to design better, more robust and risk-averse robots and autonomous machines that can think like bees – some of the most efficient navigators in the natural world,” according to Dr MaBouDi.

Secondly, Chittka and Buchmann studied bee behavior in response to fluctuations in the feel-good neurotransmitters, dopamine and serotonin. Mood-regulating chemicals increased when bees received a surprise reward of sucrose, similar to when humans enjoy a sweet treat. The improved mood led bees to have more enthusiasm for foraging compared with bees who received no reward. Alternatively, when bees were shaken in a tube or otherwise put in an anxiety-producing situation, dopamine and serotonin decreased. Buchmann reports in his book that studies have discovered bee brains “have their own internal opioid pleasure centers”.

Such findings have forced some to reconsider how bees are treated in a laboratory setting. Chittka says he would not run a traumatic experiment like the crab spider test today, but that he did not know such an outcome was possible back then. While Chittka now only conducts experiments he considers “ethically defensible,” this is not the case for others in his field, particularly when it comes to research on farming and pesticides. Part of the problem is that there are no animal welfare laws here in the United States protecting insects – or any invertebrates – in a lab setting, unlike mice and other mammals. Indeed, experiments are deliberately designed to stress and kill bees in order to figure out how much the insects can tolerate in the fields. “Many of my colleagues do invasive neuroscience experiments where bees have electrodes implanted into various body parts without any form of anesthesia,” Chittka says. “The current carefree situation that [invertebrate] researchers live in with no legal framework needs to be re-evaluated.”

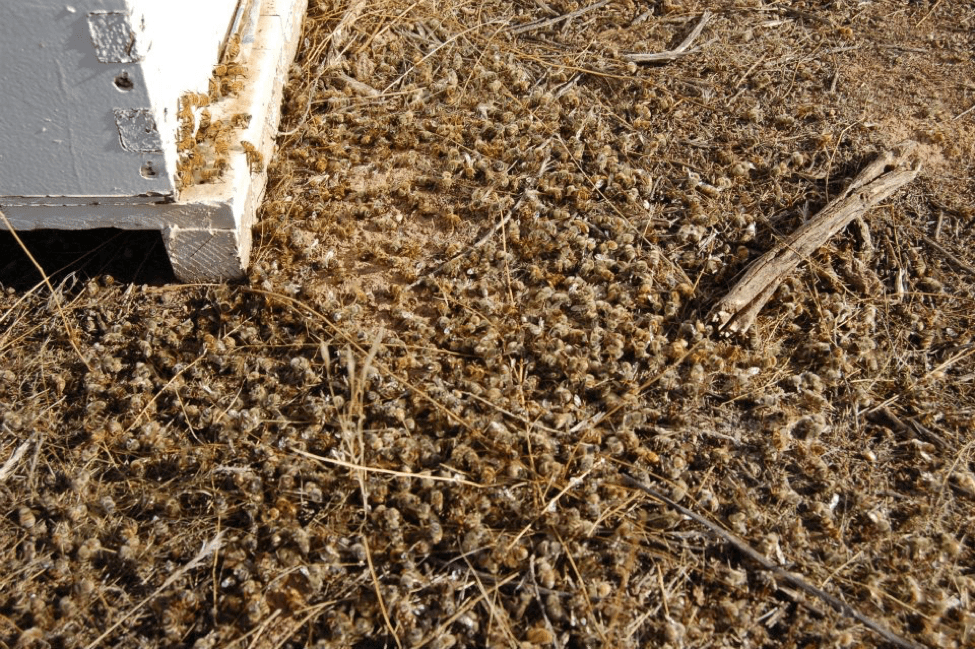

In the US, the untold numbers of bees killed for scientific research pales in comparison with the number that die while pollinating mass-produced crops, particularly almonds. But finding a way to mass-produce crops while reducing pain and suffering for bees is a daunting undertaking. If vegetarians and vegans who avoid eating animals for ethical reasons were to apply the same standards to foods pollinated by bees, they would have very little on their plates.

Commercial pollination is also big business. The California almond industry rakes in more than $11bn a year and is the third-most-profitable commodity in the state. While some agricultural operations have tried to improve the survival rate for bees by reducing pesticide use and planting more diverse forage beyond a single crop, a California startup called BeeHero is among the first commercial pollination services to directly address the issue of animal welfare. The company uses electronic sensors that are placed in hives to monitor the sounds and tonal vibrations of the colony, which BeeHero says reflect the bees’ emotional state. “There is a throb or hum to a colony that is similar to a human heartbeat,” says Huw Evans, head of innovation for BeeHero. which is pollinating approximately 100,000 acres of California almond groves. “Our sensors feel that hum the way a doctor hears a patient’s heartbeat with a stethoscope.” The data from the sensors is collected and analyzed for any variations that could indicateharms being caused by the surrounding environment.

Both Buchmann and Chittka say they have been profoundly changed by their discoveries of emotion-like states in bees. The mysterious, alien mind of a bee fills them with a sense of wonder as well as a conviction that creatures without a backbone have rights, too. “These unique minds, regardless of how much they may differ from our own, have as much justification to exist as we do,” says Chittka. “It is a wholly new aspect of how weird and wonderful the world is around us.”

So how likely is the unveiling of these ‘unique minds’, of our increasing awareness of sentience not only in honey bees but probably in all animals, likely to change our attitudes and behavior towards them? To come back to Stephen Buchmann’s statement, “Once people accept that bees are sentient and can suffer, I think attitudes will change.” Based on our current behavior as well as our history, I’m not holding my breath. Here are three examples from the thousands that I might have chosen; two are historical, one is current.

In the first few hours of July 1, 1916, in the Battle of the Somme on the Western Front of the First World War, the British Army suffered more than 57 000 casualties, with almost 20 000 dead, the bloodiest day in its history. Their commander, Field Marshall Douglas Haig, whose statue today dominates Whitehall in London, had sent the flower of British youth to death and mutilation, yet neither in his public manner nor his private diaries did he show a trace of awareness of or regret for the human suffering he had caused.

Most Americans are familiar first, with the ‘forty acres and a mule’ story, the promise General Sherman made to newly freed slaves at the end of the Civil War, only to have it reversed by Andrew Johnson after Lincoln’s assassination, and secondly with the 368 treaties signed with Native American tribes, often coerced, often broken. And yet here is an account of which we are probably less familiar. In 1918, when American soldiers returned from Europe, they were welcomed as heroes, and Congress voted to award them a bonus of $1.25 for day they had served overseas, to be paid in 1945. But in 1932, in the middle of the Great Depression, some 15000 penniless veterans camped on the Mall to petition for their bonuses. One month after the Senate refused to pass the appropriate bill President Hoover ordered the army to clear the encampment. Using tanks, police, cavalry, fixed bayonets and tear gas, a force led by General Douglas MacArthur did so … and the veterans never received their payments.

Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, author of The Body Keeps Score : Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma, writes that “(R)esearch by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has shown that one in five Americans was sexually molested as a child; one in four was beaten by a parent to the point of a mark being left on their body; and one in three couples engage in physical violence. A quarter of us grew up with alcoholic relatives, and one out of eight witnessed their mother being beaten or hit … For every American soldier who serves in a war zone abroad there are ten children who are molested in their own homes.”

If we, as a ‘civilized’ people, are willing to molest and beat our children and spouses, often under the influence of alcohol, to dismiss mass annihilation in front of enemy artillery, and to deny veterans what they had been promised, what chances do honey bees have without a voice to express their suffering? If we are arrogant enough to call ourselves “wise” (as per the sapiens in Homo sapiens) then we should be wise enough to watch, listen to, learn from and empathize with these animals who have been there, done that, but don’t wear their feelings on little t-shirts.