Welcome to this revised version of the honeybeewhisperer.simplesite blog. For this old drone it is a work in progress and has been an exercise in risk and reward, requiring new skills, lots of patience, and a willingness to ask for help.

An Introduction

I am not a scientist in any form nor by any description, even if I have a deep-seated fascination with the natural world caused, in part, by the circumstances of my early life. My formative years as a privileged white youth were spent in the Eastern Highlands of Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe – the reflection titled Muhrawa’s Hill describes one aspect of that environment. I was fortunate to teach (although I think of it more as educating than teaching ) in Rhodesia, South Africa and the United States with occasional sojourns to England and France, with a particular interest in European and African history. Over time this interest evolved into the larger educational process and culminated in group dynamics in the classroom, the latter coincidentally paralleling much of what happens in a colony of honey bees. The ultimate of this collusion is Tom Seeley’s chapter in Honey Bee Democracy in which he considers the “(L)essons we humans can learn from honey bees about how to structure a decision-making group so that the knowledge and brainpower of its members is effectively marshaled to produce good collective choices.” Amen, I say.

This is not a how-to-keep-bees blog. Those looking for a manual on good beekeeping will find plenty available that are of high quality, never mind the multitude of videos and chat sites in the cyber world. The thoughts reflected herein were stimulated by different occasions, for example my mind wandering in the bee yards as I watched the ‘girls’ (I am all-too-easily distracted,) or reading a news journal and realizing how the topic under review related as much to honey bees as it did to say societal growth or the environment writ large.

When we speak of bees, honey is the first thing that normally comes to mind – that tonic, health food and medicine that the bees arduously create from nectar. They also produce propolis, wax, royal jelly and bee venom, and, in the process of the vital act of pollination, bring back compacted pellets of protein-rich pollen to the colony. But there is a larger aspect to their life, one that is less well known but is equally as vital. In the later nineteen century the German pioneer in organic beekeeping, Ferdinand Gerstung, coined the term bien (as compared to biene, which refers to the individual bee) which he described as “an organism made up of various parts and members, all acting together harmoniously and purposefully; it is a body in which every part presupposes the existence of the whole from which the parts derive their origin and support.”

The English equivalent, superorganism, was first used by James Hutton, a geologist, in 1789, and later was the basis of the gaia hypothesiss, which suggests that the biosphere itself is a superorganism.

There is wisdom in the bien if we choose to look for it. The cosmos of a bee hive, with its organization, behaviors, interdependence and long term mission, offers an example and an inspiration as we work to reestablish our connection with the natural world and to heal the increasing divisiveness and loneliness which characterizes so much of our current society. The following essays reflect my own increasing awareness of that wisdom and the feelings of connection that come with it.

Some of the reflections are light hearted, others are more serious; some might provoke amusement, others indignation. Hopefully each in its own way will provoke a thought or renew an awareness, and might even lead to action.

The essays are organized in such a way as to flow easily – this is not the order in which they were written and my hope is that rather than feel obliged start at the beginning and read through to the end, the reader will enjoy dipping into this book at random, that each of the compositions will offer something in itself and, like a jigsaw, a bigger picture will emerge as you read.

Bee well, and do good work.

Jeremy

honeybeewhisperer@gmail.com

Meadowsong Apiary, where the Queen is strong, the drones are good looking and the workers are above average.

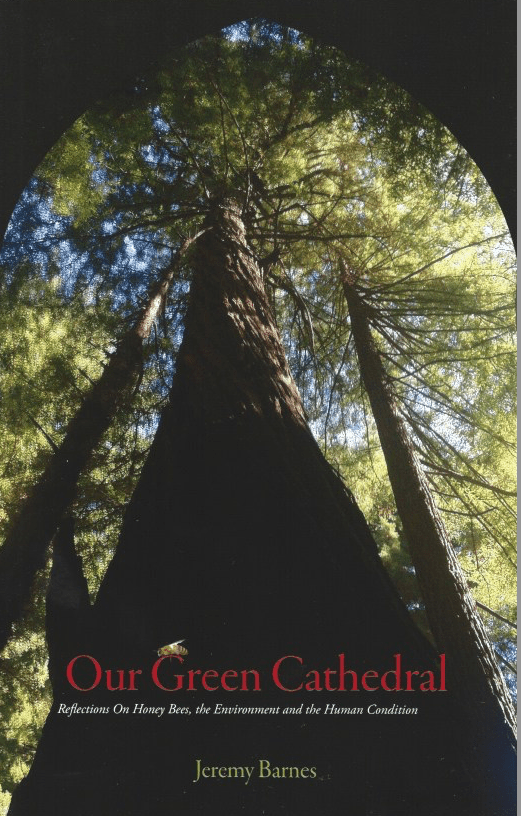

Comments from readers of Our Green Cathedral

ANALOGIES AND WISDOM PLANT A SEED

Jeremy is brilliant in the clever ways in which he utilizes the beeloved Honey Bee to incite a riot in your mind initially, simmering down to a firmer understanding of the gravity of the State of Our Garden Cathedral, laden with patina.

What a glorious day for all on the Planet Earth when Honey Bees found Jeremy; the resultant union will sharpen the readers awareness. Jeremy’s weaving will lubricate your gating channels as you view familial subjects through radical perspectives.

Awareness beeing the first step in any challenge, the analogies and wisdom contained within “Our Green Cathedral” may not dictate the steps which follow, yet, in true educating fashion, you will bee led down a path of your design with beeloved Honey Bees as thy guide. A splendid approach to displaying the darkness, yet, offering light through the canopy, seeding paths to bee involved!

– Walt Broughton

A GIFT FOR TELLING STORIES

Some of the stories are a couple of pages long, some much shorter, but each is a work that stands alone … and each is truly a work of literature art, and each is story worth telling… each is a gem worth the few minutes it takes to read, some longer some shorter.

Kim Flottum, Bee Culture, Jan 2019

METAPHOR OR TEACHER?

These essays are connected by a hum of history, insights, challenge and wisdom. Is this a book about life with bees as metaphor? Or are the bees simply our teachers? I encourage you to read the book and decide for yourself.

Meg Wheeler

A KINDRED SPIRIT

Thank you for everything you are and all that you do. Your insights are everything the world need to hear, especially now. I was delighted to be able to shake your hand at the TriCounty meeting and let you know your writing is cherished.

Deb Shepler

QUIET REFLECTIONS AND INSPIRATIONS

This morning, with my first cup of coffee, I sat in the den by the big window and started reading. I discovered what a gift this is. To be able to hear your quiet reflections and inspirations from many years of life’s experiences. Even if I didn’t know you and how deeply you care about life (big and small) – I would say this is a special and wonderful book. I look forward to sharing it with some of my closest friends.

Deb Gogniat

MODELS AND METAPHORS

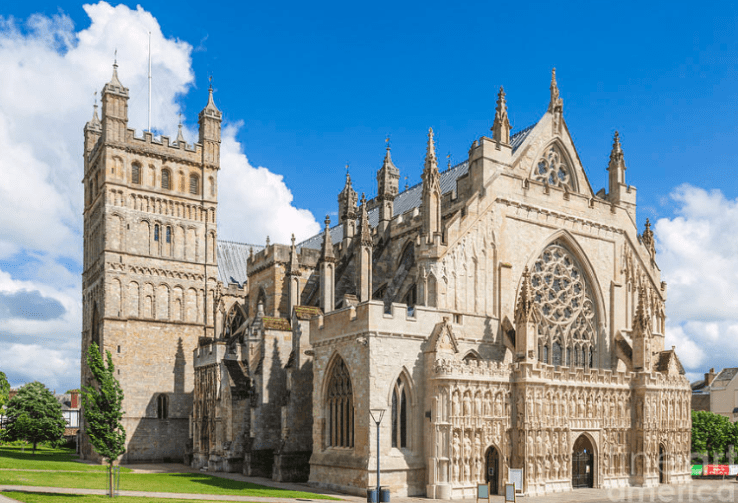

At first glance, Our Green Cathedral may appear to be simply a compilation of articles written by Jeremy Barnes for various beekeeping journals and newsletters. But, look again. This is not yet another manual on how to keep bees or even what’s the problem with bees these days – not directly. Thankfully. Rather, these are concise personal essays (95 in all) addressing the current state of our natural world and humanity’s place in it as seen through the eyes of a practiced beekeeper. Indeed, though his passion for apiculture is often the impetus for his reflections, an innate curiosity compels him to look beyond the mere surface of things to discover the histories, the symbioses, the connections underlying the big picture. He challenges our assumptions and conventional thinking, not with the power of his reasoning or the weight of his arguments; he is more subtle than that. His conversational style, his humor and honesty, his masterly employment of quotation and anecdote convincingly win the day. For Jeremy, the bee yard is a place of contemplation and insight, a refuge from the anxiety and divisiveness of the modern world, and like a green cathedral, a home for mystery and beauty. In the end, we are left with a clear impression of a man who cares deeply for the future of our planet and human-kind’s existence in it. This thought-provoking volume of essays belongs to that long history of literature which reflects on the hive and the honey bee as models and metaphors for society and the ways of the world.

David Papke

A POSTER CHILD OF BIGGER THINGS

Jeremy, I received your book about a week ago in my office inbox. My wife has immediately begun to read it. Thank you so much for this gracious gift and for the honor of being quoted in your frontispiece. We are clearly like-minded on the biospiritual unity of life and honey bees as a poster child of Bigger Things.

Dr. Keith Delaplane, Univ of Georgia

WISDOM AND ELEGANCE

Our Green Cathedral has a home on the bookshelf beside my bed, and for a long time I have enjoyed reading a piece or two as I settle in for some rest, for I find your writing thoughtful, sensible, and reassuring. Also, It has been a treat to find mention of me here and there, sometimes in connection with one of my scientific “heros”, Karl von Frisch. I thank you deeply for sending me a copy of your book.

I admire your wisdom and your range of experiences with both bees and beekeepers, all of which are expressed so elegantly in your book. One point that you make that resonates especially strongly with my own experience is your observation that when biologists give talks on genomic studies of honey bees, they express little joy in or excitement with their work. I have noticed this, too. (I think that this lack of excitement tends to be true for the audience as well as the speaker.) Probably this lack of excitement reflects the fact that when a biologist does behavioral genomics (or any kind of genomics work), he or she is investigating something abstract, hence out of sight. In contrast, when I or somebody else does a study that involves watching bees do what they do, it is almost always a strongly engaging experience. Maybe this is because this kind of work involves the parts of our brains that originally functioned to make us good hunters.

Dr. Tom Seeley

A WORLD VIEW

Your view of the world around is something I wish to emulate. UMWELT!

Jeff Berta