All five of my grandchildren have social media devices of some kind, varying in capacity and complexity. What is striking is how the three eldest, ranging from ages 10 to 16, are quick to pull out their ‘phone’ to confirm a fact, look up an image, check a spelling, or find an answer to an issue being discussed. The world is at their fingertips, literally, and they know how to access it. All five are more competent on their devices than am I on my cell phone. And yet at school they are required to relinquish their phones on arrival and listen to different people talking at them as the day progresses.

In his marvelous book, Honeybees, A natural and a Less Natural History, recently translated from the Dutch, Jacques van Alphen describes how “There is a tradition of passing on knowledge through courses and conferences, and meetings between beekeepers often give rise to lively exchanges on all aspects of the profession. The danger, however, is that age-old practices are not called into question, or re-evaluated and brought up to date… As a biologist and an outsider, I was amazed at what beekeepers take for granted. …all the new knowledge about bee behavior, genetics and evolution has not led to fundamental changes in beekeeping.”

The first beekeeping class I took, for example, was run by an elderly, competent beekeeper who was also the state inspector, and who talked at us for all but half an hour of the six classes. Looking back on the notes I took during those twelve hours, frankly I am not surprised that I lost both of my hives in the first year, nor that some were taking the class for the third, fourth or fifth time.

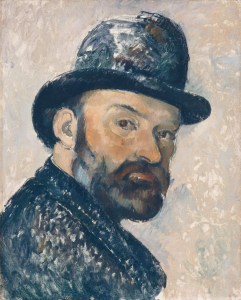

Challenging the status quo is not comfortable. I wrote two months ago about how Cézanne’s art, misunderstood and discredited by the public during most of his life, challenged all the conventional values of C19th painting because of his insistence on personal expression and on the integrity of the painting itself, regardless of subject matter. Personal expression and the integrity of the painting would seem to us to be basic, yet his works were mostly rejected in his lifetime, even as, five years after his death, he was recognized by Manet and Picasso as ‘the father of modern art.’

If the first half of the C20th was the age of physics, starting with Einstein’s Theory of Relativity and ending with the atom bomb, and the second half was the age of molecular biology, starting with the discovery of the DNA helix and ending with Dolly the sheep, then it was predicted that the first half of the C21 would be the age of the brain, and, with particular relevance to education, how we process information. Scientific journals bear testimony to the fact that the work is being done, yet it is seldom evidenced in classrooms. Indeed, if my grandfather could come back to life he would be confused by much of modern life, yet if he walked into a school he would know immediately where he was.

I would think that beekeeping classes are ideal situations for a different approach. The ‘students’ are mature, self-motivated, set their own standards, take responsibility for their own learning and, if their needs are not met or the realities of beekeeping is contrary to their expectations, are free to leave. They bring their life experiences to each class at the end of which they have a new, practical, useful, life-long skill.

Most teachers would give an arm and a leg to have students like this. And what do we do? In most cases, talk at them in a way in which, as Jacques van Alphen says, “age-old practices are not called into question, or re-evaluated and brought up to date…” It is more training than education, the difference between which was explained to me early in my career, when I was asked if I would want my daughter to have classes in sex education or in sex training.

We know that talking at people is, for most students, an ineffective way of learning. In words attributed to Mother Theresa, “There should be less talking. A preaching point is not a meeting point.” So, in a technological age, how might it be different, particularly in adult education with motivated students such as described above? There are four steps involved.

First, even before the first class meets, the task of the facilitator is to guide the participants to the literary and internet sources that are relevant and appropriate for the upcoming classes. I use the term ‘facilitator’ deliberately, in that his or her task is to facilitate the learning process, to make each participant (a term I prefer to student) responsible for his or her own learning, rather than feeling the need to teach it to them. Indeed, my favorite definition of education is by Parker Palmer – creating the community in which truth may occur.

Hence participants arrive at the first class with the basic knowledge that the facilitator would otherwise have to spell out for them, which would have consumed most of the time allocated to each class.

Secondly, the classroom seats are in a circle, with the facilitator as part of that circle. In this way the questions raised by the based on their class preparation are what they really need to know, rather than what the instructor thinks they should know. Rather than a one-way flow of information, it’s a mutual interchange of questions and responses. Again, in my experience, the process of discussing previously processed material is not familiar to many students – we have been conditioned to sit and listen to the expert – and initially the facilitator has to take more of the lead than he or she might like. But very quickly the circle takes on a life of its own, and the facilitator becomes as much a gatekeeper of the process. After all, we’re dealing with mature people, and I mean ’mature’ not in terms of age but in terms of a willingness and an ability to get the task done.

To repeat the above, “Challenging the status quo is not comfortable.” Some twenty years ago I was invited to run some classes for experienced teachers working towards their masters degrees. Thinking that I was dealing with mature, motivated students, I planned to facilitate a mutually interactive environment. It did not work – the teachers came unprepared, waited to be told what they needed to know, and were anxious to know how they would be graded. Indeed I had misread the level of maturity of the majority of the class. One of the significant advantages of the beekeeping classes is that there is no grade, no necessary affirmation from an exterior ‘authority.’ Each participant is the determiner of their own level of success.

As an aside, many teachers are notoriously resistant to change. It is not surprising; after all they chose the profession in part because of the positive, comforting, supportive feelings they themselves experienced at school – certainly I did – and want to recreate those, even though as adults they might be a generation advanced from experiencing them. They see change as a threat rather than as a way of enhancing those feelings; hence it is even more important that we have data from the neuroscientific field to combat decisions based primarily on emotions. More about that next month.

Thirdly, the latter part of the class would be in the apiary for practical application of the material discussed. My preference is to allocate three participants to a hive, to ask them to take notes using a prescribed format of what they observe as they work through it, and with each following class the triad returns to the same hive, thus following its development as the season progresses.

I can imagine the counter-argument that, at least in the first classes, a basic core of knowledge has to be created. I agree. We’re not talking about the what so much as about the how. This requires trust from the instructor-turned-facilitator; trust that self motivated students, given the tools and the responsibility, will learn more, and more efficiently, in a way that is appropriate to their own needs.

Finally, the content has to be adapted from the conventional syllabus, not least because of the increased time made available by the work done by students before classes. For example, the reading done for the final classes needs to be oriented to some of the newer discoveries about honey bees, to include bee behavior, genetics, the influence of chemicals in our environment, and the challenges of a warming climate.

“The complexity of our present trouble suggests as never before that we need to change our present concept of education,” argues Wendell Berry. “Education is not properly an industry, and its proper use is not to serve industries, either by job-training or by industry-subsidized research. It’s proper use is to enable citizens to live lives that are economically, politically, socially, and culturally responsible.”

Or, in terms of the Hebrew proverb, “Confine not your children to your own learning, for they are of a different generation.”