In the 1970’s, before the civil war in Rhodesia escalated, I devoted occasional weekends to taking small groups of high schools students to a Tribal Trust Land (not unlike an American reservation) where, by arrangement with the District Commissioner, we would meet the tribal elders, especially the tribal historian, and record as best we could their oral traditions before they were lost. Later, we were able to check some of those traditions against the archival record in Salisbury (now Harare) and were invariably impressed by their accuracy.

At one of those meetings a young lad sat with his back to a tree and wrote down the answers given by his uncles to the questions we asked (indeed, just as we were doing.) His initiative was admirable; the downside was that once we learn to write our oral memories fade as do the traditional stories that connect us with the natural world. This was reinforced three decades later on the outskirts of Nairobi, Kenya. An impressive flock of colorful birds was present every morning in the local experimental apiary, and when I asked a Kenyan college student what they were, she smiled and shrugged. I was at fault for assuming that she would be familiar with the native wild life – I would not have made that assumption about an American student on the outskirts of an American city – and she might have realized how her ‘education’ had separated her from her immediate natural environment.

In retrospect I am deeply grateful for the opportunity to have experienced a small part of rural and traditional Africa at the time I did. I have written before about the distinguished game guide who was frightened by the flashing lights on my car, or the villagers who took me in when it rained, or the elderly man on his bicycle who was deeply concerned when my sister and I were involved in a minor vehicle incident

The oral and archaeological records suggest that the ancestors of these Shona-speaking, Bantu people arrived from the north perhaps as long as one thousand years ago, which suggests there is a continuity to their history that we in the US lack. The questions, for me, are what does a culture learn from living in a place for that length time without written records, and (of course) does this relate in any way to beekeeping?

Stephen Muecke, professor of creative writing at Flinders University, Adelaide, has spent many years walking with the indigenous people of Australia, and it was his book, Reading the Country (1984) that provoked these recollections.

The oral stories that we heard in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe,) handed down from the ancestors, not only tied human and nonhuman worlds together but also animated those connections. They had been learned by deep listening and by applying them to an environment with which each person was intimately familiar. As with the Native Australians and the Native Americans, children learned experientially; rather than ask a lot of questions – respect for elders entails not bothering them too much – they learned to pay attention and acquire practical knowledge-based skills, rather than the ‘pure’ knowledge we often teach in our schools.

When Mary and I walked behind our Zulu game scout in Mkhuze Game Reserve on the trail of black rhino and he casually identified tracks in the sand made by various antelope, his skill was not sharp eyesight or a special psychological attribute so much as something embedded in generations of practices involving animals and the land.

Here’s a bit of handy know-how for you. Should you run out of food in the southern African bush, and wonder what fruits and berries are safe to eat, check the ground for evidence that the baboons and monkeys consume them.

We regard knowledge as acquired cognitively, immortalized by Rene Descartes – cogito ergo sum – whereas indigenous people remind us that knowledge is environmentally embedded, that learning happens best after students have their curiosity aroused. (Sherry Turkel, writing in her Empathy Diaries, suggests that, considering Facebook et al., the modern equivalent of Descartes, is “I share, therefore I am”!)

So how do we create an environment that provokes interest, and then cultivate the relationships essential to good learning? Sometimes it is easy : a beekeeping class or workshop, for example, normally consists of people who are already interested; when they meet in an apiary and work on a hive as a group, they are further intrigued and can explore their feelings and their discoveries with class mates.

Teaching Western Civilization II at 8:00 am to college students who simply needed the credits was a very different challenge. The difference was relevance, something which has to be nurtured and demonstrated. The norms of western civilization were seen by these college students as barely germane to their professional schedule, yet I would argue that, in the light of recent events, they are more important than ever.

Good learning happens slowly, not in 45 minute segments, and goes both ways; it is not a one-way transfer so much as shared excitement. I wince every time I read that bees are responsible for three out of every four mouthfuls of food we eat, an assertion that focuses on what we eat rather than the way the food the bees eat is poisoned because of the way we grow ours. It is this self-interest which is so destructive, penurious and hurtful.

Stephen Muecke calls this ‘living in one place, while living off another’ and offers the following example. “When multinational corporations arrive in Australia’s North-West to drill for gas and oil, they claim what they are doing is ‘good for the country’. But they don’t mean the local territory, they mean something more abstract, such as Australia and its GDP – or, more specifically, their shareholders, whose lives might be marginally improved as they live in cities or on yachts in the Caribbean. That is the difference between living in one place while living off another.”

Beekeeping is one of those activities. To do it successfully, one has to slow down, listen to what the bees are saying and observe what they need to survive. Like all living beings they have their own nature, and if we pay close attention we realize that that we are part of it: we breathe the same air, drink the same water and share the same nutrients. There is no escape; there is no better world.

David Papke shared with me an extract from Mark Winston’s Bee Time. “Initiating a dialogue requires the same attention as entering an apiary. Both stimulate a state of deep listening, engage all the senses, hearing without judging … Understandings emerge, issues clarify and become connected … Those too rare moments of presence and awareness, when deep human interactions are realized : they too, are bee-time.”

Whether under a tree in a Zimbabwe kraal, on a walk-about in Australia, on the outskirts of Nairobi, or looking for rhinos in Kwa-Zulu, that’s not a bad definition of good education, and we find it all with the bees.

No doubt everyone’s adventure with beekeeping is different. Ideally it starts with a good beekeeping class, combining the theory and the practice, followed by a five year period in which, with the help of a mentor, one becomes familiar with the various storylines of a colony of honey bees. What happens next depends first on why one keeps bees, secondly on one’s level of curiosity, and thirdly the extent to which one exposes oneself to current research, thinking and practices.

In retrospect, the class I took initially was not a good one. The presenter was knowledgable but did not have the communication skills that are an integral part of inspired teaching, and there was no logic behind the curriculum. The tip-off was the number of participants who were taking the class for the third, fourth and even fifth time. This is a reminder that we need somehow to assess the skill levels of those who volunteer for presentations under the banner of our various associations. Their willingness to give of their time and share their knowledge is cherished; the question as to gauging their levels of competence is delicate but consequential.

Also involved with this class was a local supplier who had preordered all the paraphernalia, including packages, that the participants might need. I can recall no discussion of alternatives, nor of the pros and cons of packages.

I was fortunate to stumble on the assistance of a mentor during my first year, which proved vital. It was not a service provided by the local beekeeping organization which, at the time, was a rather small, stolid group which did not offer much outside of the once-a-month meeting.

After six years of practical, hands-on experience supported by a reasonable amount of reading, and with Mary’s support, I committed to attending Apimondia in Montpellier, France, in 2009. It was inspirational, stimulating and self-affirming; I returned not only with increased knowledge but also with the determination to take my honey bee management to a new level and to share both with others.

In the following eleven years there were a series of stimuli, one of which, in 2018, was what Tom Seeley calls Darwinian Beekeeping, and which I prefer to think of as regenerative beekeeping. In essence, Dr. Seeley suggests that beekeeping has become increasingly designed for the benefit of the beekeeper rather than the health of the bees, and he has examined feral colonies to survey the conditions that bees choose for themselves, given their druthers. David Papke had been similarly inspired, was a step ahead of me in coming up with a hive design that was more bee friendly, and we spent a year re-designing our hive bodies and presenting, with differing levels of success, our reasoning to some local bee organizations. The reactions ranged from outright dismissal to skepticism to enthusiasm to excitement.

Initial results are encouraging, but it is a small sample and early days. The question is, what kind of changes in management might supplement the re-design of the hive? It is important to note that at each of the three occasions on which I have been fortunate to hear Tom Seeley present his findings, he stresses that this is a concept for hobbyists, possibly for sideliners, but not for commercial beekeepers, whose objectives and financial commitments are less likely to allow for experimentation.

Too often Darwinian beekeeping is interpreted as survival of the fittest, requiring a ’hands off’ or ‘ live and let die’ approach by the beekeeper. Far from it. In fact, if the goal is to keep locally adapted, healthy bees without resorting to chemicals, it is right in line with my objectives at this point in my calling. If people can be seen as either butterflies (sitting still, spreading their wings, displaying their beauty and attracting attention) or bees (flitting from flower to flower, cross-pollinating) I am the latter, consistently attracted by different ideas and visions, flying to them to enlarge my foraging area and the diversity of food in my brood nest.

Earlier this year David came across a series of three articles written by Terry Combs and published in ABJ, August, 2018, and Jan and Feb or 2019, and which fused all that I had learned over some 20 years and gave it a distinct focus under the bigger umbrella of restorative beekeeping. This is the most recent stimuli in my beekeeping journey, I have committed the next three years to it, and am enthusiastic as to the challenges and opportunities it presents.

None of the fundamentals involved are particularly difficult or different. The first is to keep good records in order to assess queen quality and colony sustainability. Terry, having once bred guppies, gives example of the complex evaluation sheets he uses; we have devised something a little more simple, with a quantitive assessment, that can be used with each colony over a year, culminating in a numerical decision as to how to proceed with those bees the following year.

The process begins by critically selecting the colonies one wants to over-winter, to the extent of culling the queen in any colony that lacks the resources or mass of bees to survive successfully and combining the remaining bees with a strong colony.

In the spring, the beekeeper selects breeder colonies for queen propagation, which might be either ones own hives that have a persistent record of success (hence the importance of those records) or a feral swarm. Ideally, once established, a beekeeper should never have to purchase a queen; indeed, the active sharing of queens by local beekeepers committed to this program is the best source of all. If a new outside queen is needed, perhaps for genetic diversity, it is vital to realize that ‘locally adapted,’ means more than simply having survived one or two winters. The queen supplier needs to explain the testing, evaluation and selection processes the bees have undergone.

Swarming is an integral part of the honey bee cycle. Rather than trying to prevent it, one can use the swarming impulse to make splits once there are queen cells with larvae. The thinking is that bees make specific choices when it comes to developing queen cells, whereas our choices via grafting are random. The nucs made by these splits can contain either the queen from the original colony or well developed queen cells.

Drone quality is an increasing topic of conversation. Terry argues in favor of establishing drone mother colonies that have the desired traits. In York County we do have a community apiary which could conceivable serve as a modified drone mating yard as established by Brother Adam on the moors of Devon, but he was breeding a specific sub-species of honey bee and therefore he wanted his queens to mate with drones of a certain type. That is not our issue. We simply want our queens to mate with quality drones.

That leads to the question, what is a quality drone? We know what qualities we want in a queen, but those in a drone are more difficult to quantify.

Indeed, does it matter? Jurgen Tautz , writing in The Buzz About Bees, argues that the desired quality comes in the drones that succeed, among hundreds, of mating with a queen, and then again in the selection of sperm to mate with queen’s gametes. He further points out that queens transported to a different area (eg. a mating yard) had a much lower success rate than those in local mating stations (eg. an apiary.) The reason, he suggests, is that the queen is accompanied by a retinue of forager bees who know the area and escort her to and from the DCA.

Terry is not specific in terms of ‘desirable traits’ but does stress the need for active feral colonies and to introduce occasionally new stock for genetic diversity.

The takeaway is that if we follow the Darwinian process of not needlessly removing drone cells, and as we develop better and stronger colonies using Terry Combs’ selection procedures, we can assume that the drones will be equally robust and will provide the quality that we need without having to develop specific drone mother colonies.

The final step is to re-queen each original colony with the best young queens from the splits. Each new queen can be evaluated after a full brood cycle, realizing, as Terry writes, “Rigorous and timely culling is hard but necessary. If you truly want to help bees, you’re going to have to adopt nature’s hard stance against the weak, deformed and inferior …”

We should stress that this system does not preclude the use of organic chemicals as part of an integrated pest management system. In the specific case of excessive varroa counts, options include freezing the brood, replacing the queen, combining with a resistant colony, using an organic treatment, or in the worst case scenario, eliminating the entire colony.

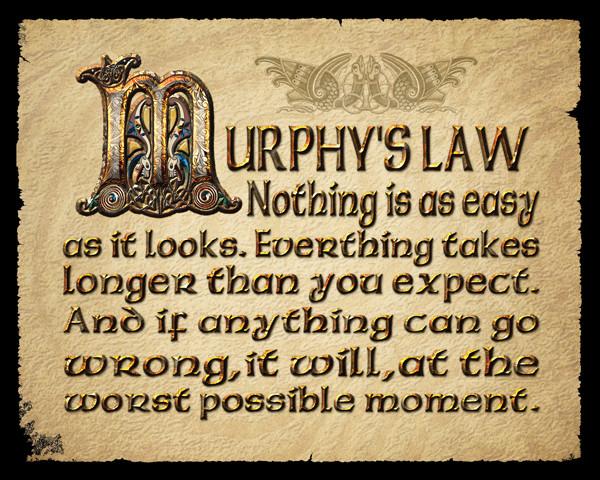

So that is where I am at. The next three years seem to be taken care of, but as we all know, if you want to make God laugh, tell Her your future plans …