Part ll of lV

“I dedicate myself to study the lesson of avoiding killing living beings.” Such is the first Precept of Buddhism, as outlined last month. The second Precept, “I refrain from taking what is not given,” is more than simply not stealing; it is a call to live with integrity, respect and gratitude for what we have while honoring the boundaries set by others. If we take what is not freely offered, whether it be in material terms, time, energy or ideas, we sow the seeds of greed that fracture the delicate web of interdependence. Exploiting shared resources is to act with a mindset of entitlement that in turn distances us from contentment.

By comparison, when we cultivate generosity, when we create a life rooted in gratitude, we find that true wealth lies not in material possessions but in the trust and kindness that we foster.

Honey bees of course take what they need in such a way that not so much as a leaf is harmed; rather, through the act of pollination, that strong desire to endure, common to all species, is converted into action. And the dynamics of a colony are such that foragers communicate as to the immediate needs of the hive – pollen, nectar, water, propolis, each of which is freely offered to the bees – so that there is a stasis of resources, a balance, without unnecessary waste of materials or effort. Only recently have we realized the vital role of the tremble dance in maintaining this.

Surely critical to beekeeping is knowing how much of the resources of a hive one can take without affecting adversely the future and health of the bees. Greedy beekeepers do not, in my experience, last very long. Far from being entitled, we as beekeepers have a responsibility to nurture the critical environmental interdependent web on which both we and the bees depend. And this, in terms of the second Precept, is the big picture – the environment is telling us, very powerfully even as we still cannot hear it, that for too long we have been taking more than the earth can give. The solution lies in each one of us : if our species is to endure we need to be mindful and compassionate on a constant basis as to what our planet can give and what we can rightfully take. There are no excuses. In this, honey bees are our teachers.

The third Precept is often translated as “I refrain from sexual misconduct,” even as a literal translation of the original Pali, Chinese and Tibetan texts, according to Phra Anil Sakya, suggests “I refrain from using the five senses to violate basic rights.” In beekeeping terms, this translates as managing our colonies in a way that respects the bees’ natural habitats and behaviors as they have evolved over millennia. An interesting debate might be whether we violate such rights by producing queens via artificial insemination, partly to produce more queens and partly to select for certain traits in the colony. There is evidence that when workers choose an egg to develop into a queen,their choice is not random, whereas ours is based primarily on the age of the larvae and the amount of queen jelly in the cell. Would this qualify as sexual misconduct on our part, or does the latter intent (behavioral traits) justify it? But there is a larger issue which is sufficiently complex yet important enough to justify its own Corner, which I will address next month. It refers to a beekeeper’s decision to manipulate a queen or a colony (eg. wing clipping, queen larvae removal) and the long term impact on a colony.

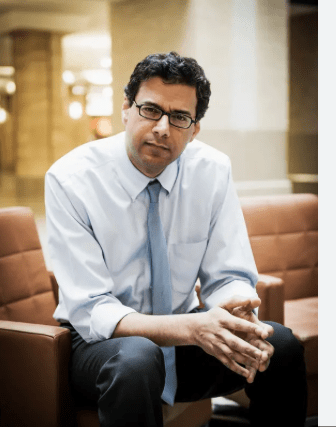

“I dedicate myself not to tell falsehoods,” the fourth Precept, means speaking truthfully and honestly, but it also means using speech to benefit others rather than only ourselves. This requires first that we are mindful of what is true, and secondly that we examine our motivations when we speak to be sure there isn’t some trace of ego or hidden agendas behind our words, or a need to feel morally superior. We know it when we hear it, and the example that comes to mind immediately is Dr. Tom Seeley.

Sometimes we need to speak up to stop harm or suffering. More than twenty years ago, riding along with the then bee inspector on his daily inspections, he made a comment that has stayed with me : ”Some people simply should not be allowed to keep bees.” But of course we don’t say so out loud. The late Chogyam Trungpa called this “idiot compassion,” a form of which is hiding behind a facade of “nice” as a protection from conflict or unpleasantness. The lesson is that one cannot be honest with others until one is honest with oneself, which is integral self-enlightenment.

We are familiar with the different moods that a colony can display over the course of a season. When it goes badly I blame the weather, the temperature, bad genes, Africanized bees … anything but myself. And yes, there are colonies that are consistently defensive and need to be acknowledged as such. It is equally possible that the super-sensitive antennae of honey bees can detect pheromones that we too emit. Sometimes I inspect a colony because I feel “I should;” it is a begrudging obligation rather than one filled with joy, and neither the bees nor I enjoy it.

Some five years ago a nephew, who is a neurologist, was visiting and asked to see the inside of a colony. Normally I don’t wear a veil (although there is one at hand ‘just in case’) and he opted to do the same, insisting he wasn’t scared. The colony was docile, except for one bee who stung the visitor on the lip, and it hurt! Afterwards he conceded that he had in fact been scared but ‘was man enough to deny it.’ One bee at least was not fooled, triggered perhaps by the increased amount of carbon dioxide that my guest was emitting. What might have changed if he had ‘chosen not to tell falsehoods’ from the outset?

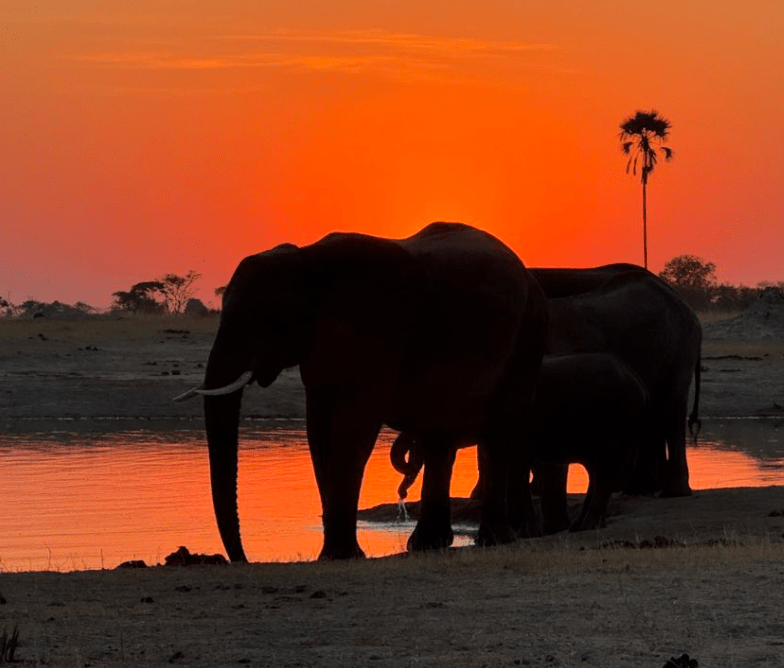

What might all of this mean in bigger terms? The Walk for Peace by the Buddhist monks and their dog, Aloka, begun in November last year in Fort Worth, TX, attracted significant attention – over one million followers on cyber media and the thousands who lined the roadside, some of whom had traveled significant distances to be there. Why this attention? One possible reason is that the monks, who did no more than walk with gratitude and intent, had an authenticity, both individually and collectively, that we all yearn for, not least in these complicated, conflicting political times. There was also in their every action a simplicity, a purity, a clarity, even an innocence, which we once knew in the honesty of childhood and only now realize that we miss it. There was no preaching, no capitalist agenda; the monks focused on the present, on gratitude, on intent and inner calmness (Aloka has become a symbol of that calmness) and tens of thousands of people found it so compelling that there were many tears as the caravan passed by. It was a reminder that the path to awakening lies not in grand gestures but in the quiet, consistent care we bring to each moment, in association with the power of human community.

The fifth Precept of Buddhism is to refrain from consuming intoxicants, which can impair one’s judgment and mindfulness. The emphasis is on the importance of maintaining the clarity of mind necessary to make wise choices and avoid causing harm to oneself and others. “…the path to awakening lies not in grand gestures but in the quiet, consistent care we bring to each moment …” not least when working with honey bees.

Beekeeping allows all people, regardless of faith, culture or background, to come together in a spirit of compassion, mutual respect and understanding. At its best it offers a glimpse into a peaceful, efficient, community, just as nature intended; something that we might have briefly experienced in the innocence of childhood and something that we desperately miss and want to recreate even by proxy, not in grand gestures but in the quiet, consistent care we bring to each moment. Does this explain the calmness that can come from being surrounded by honey bees? Or the satisfaction that comes with a greater understanding of our charges and the questions that we are led to ask about the relationship between honey bees in a colony and people in a modern community? Perhaps, as with many pursuits, beekeeping offers a chance for us to find relief from the pressures of the modern world by practicing these Precepts, even unwittingly, and experiencing the joy, the contentment, the ‘internal journey towards enlightenment’ if we should be so fortunate.

New beekeepers want prescriptions rather than precepts. How often have we been asked, “What do I do next?” as if there is some kind of specific formula for each occasion. What if we began our bee classes with appropriate precepts, which set ethical standards in which to operate, and then provided opportunities in which they could be practiced? My intent is to end this four part series with some possible precepts, hopefully as the beginning of a discussion.

The Venerable Bhikkhu Pannakara, who led the Walk of Peace, wrote, “We walk not to protest, but to awaken the love of peace that already lives within each of us. It is a simple yet meaningful reminder that unity and kindness begin within each of us and can radiate outward to families, communities, and society as a whole. Our walking itself cannot restore peace in the world. But when someone encounters us – whether by the roadside, online or through a friend – when our message touches something deep within them, when it awakens the love for peace that has always lived quietly in their own heart – something sacred begins to unfold. This is our contribution – not to force healing upon the world, but to help nurture it, one awakened heart at a time.”

Replace the word peace with the word nature, and his words are equally inspirational.