My father was born in an age when the lack of a formal education was not necessarily an obstacle to personal success. He left school in Devon, England, aged 16, and retired some 45 years later, not only responsible for the maintenance of the national roads of an entire country but well respected by his peers, all of them degreed engineers. No doubt, four years of building roads and bridges to allow the British forces to retreat before, and then advance after, the Japanese forces in Burma, was a vital part of his education.

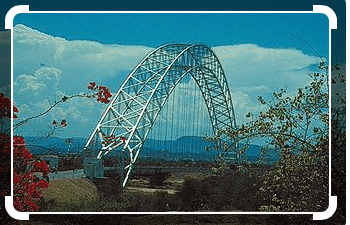

He spent week-long trips inspecting roads and visiting road crews, and over school holidays I would often accompany him. My favorite memory is lying in the back of the station wagon parked at the Birchenough Bridge Hotel, alongside the Savi River, under a tree interlaced with nests of masked weaver birds, watching for shooting stars in the vivid African night sky. The masked weaver is a fascinating creature. The males, for example, build nests at the very ends of the branches of thorned acacia trees so as to make them inaccessible to snakes in particular. The nest are architectural marvels, each consisting of several rooms, all but one of which are decoys. When he is finished – some 12 to 14 hours of work in all – his partner inspects it. Should it not meet her approval she rips it apart and he promptly builds another … until such time as she is satisfied.

Another memory, less pleasant but probably more important, was when we were driving between road camps and my father decided to offer some simple mental math problems involving speed and distance. A typical example might be, if we are driving at 60 mph, how long will it take us to travel 30 miles? I couldn’t do it. The more I tried, the more he explained, and the more frustrated I became. Emotion superseded any ability on my part to think rationally . He could not understand why it was so difficult. The reason? I did not understand that miles per hour meant how many miles one traveled in one hour. It was a non-understanding of the word per. It was a simple as that.

That was some 70 years ago, and I have not forgotten it.

Ironically, when I was driving the 1400 miles to university twice a year, the speedometer in my car didn’t work (a broken cable, I discovered eventually.) Thus I spent considerable time using the mile posts and a wrist watch to calculate my speed, by which time I understood only too well what per meant!

The point is, especially as that time of year approaches when bee classes start, we should never assume that what is obvious to us is equally obvious to those new to the craft. Beekeeping, like most things, has its own language, and there are terms that we take for granted – larvae, pupae, comb, propolis, foundation, frames, EFB, AFB, varroa mites – which may be new to many in the class. Some will ask; others will keep quiet and hope they can figure it out from the context. It doesn’t help when some terms are mispronounced; for example, the first instructor I had pronounced honey bee comb as cone.

Sometimes it doesn’t matter. For example, I have absolutely no idea what http, or jpeg, or hrl, stand for, nor do I need to know. If I was in a computer 101 class it might be entirely different but, as it stands, I can use my computer without having to know how to code or what the abbreviations mean. In the same way one can drive a car without understanding how the engine works, or realize the implications of the law without having been to law school. I recall vividly teaching European history to a group of 16 year olds in 1970. One of the students, sitting in the back, right hand desk, put up his hand and asked what the difference was between domestic and foreign policy. I was stunned – these were terms we had been using all year – and essentially I did not answer, assuming he was pulling my leg. Now I know better, and am ashamed of my callous response.

Beekeeping does not fall into the computer, vehicle and legal categories. The essence of the beekeeping class is graduating from simply watching honey bees to being able to understand their behavior and thus to intervene appropriately and for their benefit. It is this comprehension of which language is so important a part. A pertinent example might be Keith Delaplane’s latest book, Honey Bee Social Evolution, not only because of his superb use of language but also because his explanations of the evolutionary processes that have led to current bee behavior enlarge my understanding of what I see in the hives and thus impact my interventions, if any.

A technique for an instructor is to acknowledge at the very outset that he/she might inadvertently use terms that are part of the beekeeping experience but which are unknown to the class. In such an event it is important for class members to speak out; it will not only allow for clarification for the students but will provide valuable insight for the instructor as to their level of comprehension.

The Birchenough Bridge, taken from the hotel.