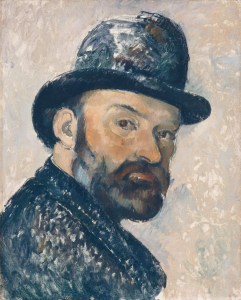

Paul Cézanne always knew he wanted to be an artist. At his father’s urgings, he entered law school in his home town of Aix-en-Provence in the south of France, but after two years, aged 22, he withdrew and went to Paris to pursue his artistic dreams. Rejected by the École des Beaux-Arts, he returned home to work as a clerk in his father’s bank.

He returned to Paris the next year, was rejected yet again by the École, and his paintings were turned down every year by the Salon de Paris until 1882, when he was 43 years of age. None of his work was put on display until he was 56, when he had his first one man show. Two years later, 1897, a piece was bought by a museum in Berlin, and in 1899, when he was 60 years old, his work finally started to sell. He died seven years later.

A year after his death a retrospective of his work was mounted in Paris and he was recognized as one of the founders of modern art. “Cézanne is the father of us all,” Matisse and Picasso declared.

Cézanne’s art, misunderstood and discredited by the public during most of his life, challenged all the conventional values of painting in the 19th century because of his insistence on personal expression and on the integrity of the painting itself, regardless of subject matter.

This story is told by David Brooks in a recent article in The Atlantic in which he seeks to understand those who make their mark later in life, whether it be Copernicus, Morgan Freeman, Isak Dinesen, Julia Childs, Charles Darwin, Winston Churchill, Alfred Hitchcock, Colonel Sanders and a host of others. Space does not allow elaboration of each one; suffice to say that Churchill was mistrusted as a political rebel and outlier until 1940, when he became Prime Minister at the age of 66, Juliet Childs enrolled in a French cooking school aged 37, and Colonel Sanders invented the recipe for Kentucky Fried Chicken aged 62.

Society today is structured to promote and reward early bloomers. By the age of 18 most of us have been pigeon-holed by grades and SAT scores, some zoom to prestigious academic launching plans and some, such as Bill Gates, Marl Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Taylor Swift, Michael Jordan and Lebron James, take other routes.

But there are also successful late bloomers; indeed the average age at which Nobel Prize winners made their crucial discoveries is 44, which means that approximately half of them did so well into the second act of their lives. In essence, they focus not on the finished product so much as on the process of learning itself. They see their lives as a process of trial and error so that the quality of their work peaks as they age.

In Late Bloomers, Rich Karlgaard teases out the traits that distinguish early from late bloomers. Most of our schools and work places, for example, are based on extrinsic motivation – work hard and you will be rewarded with good grades, higher salaries and performance bonuses. Early bloomers are good at meeting external standards, at following other people’s methods and at pursing goals determined by others. Late bloomers, by comparison, are bad at being what has been called ‘excellent sheep.’ They often feel unfulfilled at school or work and can be contrary if not rebellious. Winston Churchill reflected that “Where my reason, imagination or interest were not engaged, I would not or I could not learn.”

Our culture encourages people to specialize early – concentrate on one thing and get really good, really fast. Late bloomers, by comparison, need a variety of experiences even if it means frequently changing jobs and developing a reputation for inconsistency or unreliability. But this is when they are developing what has been labeled ‘diverse curiosity,’ the benefits of which become evident once he or she draws on the breadth of their knowledge to put discordant ideas together in new ways.

Late bloomers teach themselves – they enjoy the cognitive process (Leonardo da Vinci is the poster child) and being too old for the traditional educational system, nor wanting the restrictions built into it, they become fascinated and absorbed by the pleasures of concentrated, voluntary efforts in which they are free to plot their own course and to change their minds and their objectives without recrimination. And to this they bring their life experience, otherwise called wisdom, in particular the ability to see things from multiple points of view and to sustain the tension that often exists between them.

Finally, late bloomers never cross the finish line and relax. Age does not diminish their curiosity; “They are seeking. They are striving. They are in it with all their heart,” to cite David Brooks.

Honey bees clearly are not late bloomers! Each bee follows a genetically driven master plan that determines their development and their role in the bigger society, Similarly, in the African society with which I grew up, the social norm was ‘to keep down with the Jones’s.” As one tribal elder said to me, “If one blade of grass grows higher than the others, we cut it down.” With significant credibility given to the power of spiritual forces, the credo was each individual is born with a talent with which to serve society, but to exceed that is a sign of a malevolent force. Initially this presented a significant challenge for European-trained teachers in some African countries. I recall a District Commissioner describing the traditional belief that tribal people accumulate knowledge as they age, that they do so at the same rate, hence the significant respect given to elders who, because of their age, were also the most knowledgable. Recognizing differences in students, or trying to stimulate them through grades, initially proved counter-cultural and unsuccessful.

And a thousand years of western civilization was not much different. From the fall of Rome to the Renaissance was a millennia of remarkable conformity. The life of the common man in 500 AD was little different to that of his successors one thousand years later. The purpose of art, for example, was to glorify God, and works consisted almost entirely either of moral pieces warning of the dangers of sin, or of depictions of biblical figures and events invariably set in contemporary times. For me, this is why Leonardo’s Mona Lisa is so revolutionary For the first time in a millennium, a major artist had painted a woman in her natural beauty and enchantment, without traditional Christian artifacts. It was a celebration of humanity set in the harshness of the natural world. And in terms of late bloomers, the exact date of the painting is unknown, but Leonardo seems to have started work on the Mona Lisa when he was in his early 50’s, and continued work on it or various editing of it, until he was in his mid 60’s. Late bloomers are seldom fully satisfied “”They are seeking. They are striving.”

None of this is to denigrate those (and there are many) who focus on one issue, for example keeping honey bees, and find satisfaction in a particular method that works well for them without any need to deviate from that. One of my uncles was a spitfire pilot in the Second World War, after which he returned to the town and house in which he grew up, never learned to drive a car, and spent his vacations working on his allotment or fishing in the river Exe. When I first met him, in 1980, he impressed immediately with what is often described as ‘serenity’; he was deeply content and wanted for nothing … and I was a little envious.

Looking back at my career, I changed schools every seven or eight years whereas many of my colleagues remained (and maybe still are) at the same school for all of their teaching career. Two things are clear in retrospect. First, that after seven years I felt I had gained, and offered, all I could from that particular system and needed a change if I was to remain vital. Secondly, the wide variety of extra-curricular activities that I organized, ranging from evening clubs like Toastmasters or a History Society to three week bike tours in Europe, were not so much stimulating the students, as I thought, but were providing me with the challenges, the inspiration and the fulfillment that I needed.

As a beekeeper, I am restless, always seeking stimulation, and enjoying the process a much as the product. Which brings me to my hypotheses – that many beekeepers are late bloomers whose life experiences have brought them to this hobby. They are extrinsically motivated, set their own standards, take responsibility for their own enlightenment, enjoy the learning process and the feelings of accomplishment that come with it, and are surprised by the unexpected exposure to a variety of associated issues such as plants and pollination, chemicals in agriculture and their impact on animal life, the amazing society that is the world of a honey bee hive with its relevance to our own community, whether local or national, and indeed, the local impacts and challenges of a changing environment.

Perhaps it is the constant provocation and challenge provoked by such questions that cause some to stay involved, with the comfortable realization that every answer leads to yet more questions.