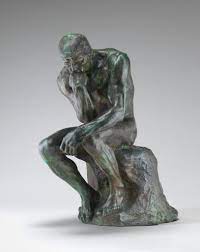

Two scenarios share a common theme, despite being separated by distance and time. In the first, an elderly man walks to the public square where he questions young men on esoteric matters such as the nature of justice. In the second, reflecting on what was possibly the major achievement of his life, a venerable diplomat says, “It was 700 days of failure and one day of success.”

The first is Socrates in the agora of Athens almost 2500 years ago, as described by his student, Plato. In Plato’s early dialogues, confusion is considered to be the beginning of genuine enquiry, rather than a disagreeable feeling and a waste of precious time. With their assumptions challenged, the young Greeks were left in a state of confusion which, in Socrates’ eyes, was the first indispensable step of any true enquiry into the truth : ‘[Having] been reduced to the perplexity of realizing that he did not know … he will go on and discover something.’

The second is Senator George Mitchell in April of this year, describing the two year process that led up to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, which brought an end two decades of sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland. Known as ‘The Troubles,’ during which 3600 people died and countless more were seriously injured, Protestants (or Unionists) fought to keep Northern Ireland part of the United Kingdom while Catholics (or Republicans) wanted to be part of the Republic of Ireland. George Mitchell, a former senator from Maine and Clinton’s ambassador to Ireland, served as chairman of the Northern Ireland peace talks which brokered the historic agreement.

What did he do for those 700 days? On the surface, very little. He did not socialize with either side nor did not he speak much in public. What he did do was listen, and by doing so he honored the state of national confusion without offering preconceived solutions, eventually establishing trust with both sides. As he later said, “I tried very hard to be fair and nonpartisan. I’d had experience — six years as majority leader of the U.S. Senate gives you some practice in trying to bring people together – and so while there was considerable opposition to my serving as chairman at the outset, by the time we finished, we were all very friendly and we’ve remained personal friends really for the rest of [our] lives …”

In a seminal paper published in APA PsycNet in 2003, the psychologists Paul Rozin and Adam Cohen asked college students to observe facial expressions and describe the emotion being expressed, as well as the facial movements involved. To their surprise, the most common descriptor was confusion, even though it is not a category in standard taxonomies of emotion, let alone part of the set of basic emotions recognised by psychologists. The question then became: what is the nature of confusion and what is its use?

Most of us encounter confusion on a daily basis, ranging from trying to make sense of an unexpected piece of national news to understanding the reasons for an inter-family quarrel. The world is an inherently and increasingly confusing place, not least in the post-truth era where fake news is ubiquitous : increasingly we encounter statements and problems that do not make immediate sense because they do not fit with previous patterns we have experienced. Overcoming this results in real learning.

New beekeepers tend to believe the answers lie essentially in memorization or rote learning. After all, that is how many of us got through school. Some, for example, in an early inspection, will encounter stimuli that are new and unexpectedly confusing, to the point that his or her ability to make sense of them using current knowledge is low. The consequent frustration can decrease motivation to the point of giving up altogether. Too big a piece of the puzzle is missing and it feels that the game is not worth the strain. This is what researchers call ‘hopeless confusion’.

Complex learning tasks require both a solid knowledge base and the confidence and ability to apply that knowledge for diagnosis and possible solutions. In such instances confusion can act as a motivator. As an aside, how often do we deliberately allow for confusion in our school classrooms (as compared to chaos) even though the learning from successfully solving a challenging problem can be deeply rewarding? Because of my background, I would add that the history of this country is confusing, and we simplify it at our peril.

Consider, for example, a new beekeeper who, inspecting a hive, finds she cannot see eggs. Her knowledge base tells her why the presence of eggs is important; now she has to apply that knowledge to determine why they might be absent – perhaps she just can’t see them, or the queen is not laying, in which case why, or there is a brood break because of recent swarming, or the bees are in the process of superseding the queen. Amid this uncertainty she can adjust the inspection in a way that will help identify the likely cause which in turn will lead to appropriate solutions, ranging from doing nothing and coming back in a week’s time, to initiating enquiries for a new queen. And in the best case scenario, she will have access to a mentor who can help connect her observations with potential responses.

Nor is this confined to new beekeepers. For example, I have a colony that did well last year, came through the winter strong, yet had a mite count of 12 in early April and 18 in late May. My intent was to remove the queen, treat the mites once all the brood had emerged, and add a new queen with better genetics. Yet, despite three searches, I cannot find her. The bees are calm, which suggests they are queen-right, and there are neither eggs nor signs of a virgin, such as a queen cell from which she has emerged. I know what to do – add a frame with one-day-old larvae and, after three days, check to see if the workers are building queen cells around one or more of them; what I don’t know is why the colony is in this state.

Similarly a colleague and neighbor had significant swarming from his hives last year, continuing this spring with 21 swarms from 12 hives. It doesn’t seem to be an issue of the environment providing excess resources (his apiary and mine are less than a bee-mile apart,) nor is it likely all of his queens have a high tendency towards swarming. Is it a management issue? If so the answer in not immediately apparent, and he is approaching it rigorously, asking valid questions and making good notes, including graphical representations of the relationship between temperature, rainfall and swarms in his apiary.

So he and I are confused, and happily so, the recognition of which is motivating a deeper kind of enquiry with more thorough information-processing, and without trying to hasten a conclusion. An eventual solution will increase the chances of overcoming the next obstacle not by working harder so much as by working differently. The proviso is the 85 % rule – the optimal degree of difficulty to heighten focus without leading to a sense of helplessness, is a task in which learners succeed 85% of the time.

Research in neuroscience shows that encountering a problem while learning a new skill such as beekeeping enhances neuroplasticity in our brains, which make us more alert, focused and cognitively active. My guess is that most experienced beekeepers can relate to this process, in particular the feeling of being more focused, more aware, more alive, when working with honey bees. Enhanced neuroplasticity is why retirees are frequently advised to take up a new hobby or interest, and might be why many beekeepers turn to this hobby later in their lives.

But I don’t want to stop here. I want to argue that there should be legitimate confusion on a much larger scale. Nicola Broadbear, the director of Bees for Development, writing in the Spring, 2023, issue of the Natural Bee Husbandry magazine, suggests that “(P)eriods don’t become defined by the styles for which they are known until long after they have ended, and maybe the past fifty years will be regarded as the beekeeping crazy era, when it was thought that we could keep honey bee colonies in sub-standard housing, shift them from place to place, reduce the range and abundance of available flora, stop them reproducing normally, take away all their honey and feed them white sugar instead, treat them with chemicals, and we then complained that they became sick and died!”

Reframing confusion as a positive and valuable feeling invites us to rethink some of our accepted practices. In our current world, information, data and pre-made solutions are so readily available at the tip of our fingers that we deprive ourselves of opportunities to enhance our brain plasticity by contemplating possible answers of our own. Instead of trying to come up with hypotheses for our questions, we put our brains on pause while we type in the question for Uncle Google and wait for the answer to be delivered on our phones. To cite Vidya Rajan (again) in a personal e-mail, “. So much information, but so little thinking/rumination because information just “is there”. No analysis, no inference, no hypotheses. Just answers. Boom.”

And yes, clearly there are times when confusion is inappropriate – I don’t want the pilot flying my plane, nor the surgeon about to operate, to be confused; my guess is that it was the hours of training with different unexpected scenarios that allowed Sully Sullenberger to execute an emergency landing of US Airways Flight 1549 on the Hudson River, in January of 2009, in which all 155 passengers and crew survived.

How might Socrates and George Mitchell approach ‘the bee problem’? I imagine the former would ask persistent and demanding questions prompting us to examine what we have come to take for granted, until we were open to questioning the issues raised by Nicola above – the structure of a modern hive, the mass transportation of bees, the lack of natural resources, feeding sugar and exposure to chemicals. George Mitchell, by comparison, might gain the trust of the various sides involved, from commercial beekeepers to hobbyists, agribusiness to small gardeners, until he judged that exposure to opposing points had motivated sufficient empathy on all sides so as to prompt a higher level of focus and an increased probability of success.

My expectation is that when you read above the request to students by Rozin and Cohen to observe facial expressions, and that the most common description was confusion, your immediate impression was that this was a negative. In fact it was a positive. Productive confusion triggers us to think more deeply and to avoid premature closure, despite the frustration. Contrary as this is to current cultural trends which promise immediate gratification, confusion is an indication that our brain is preparing to focus more deeply, to process more thoroughly, and thus offer us a better chance at learning something valuable. I for one am grateful, first, that honey bees frequently invite me to learn something valuable (‘beekeeping is a gateway drug!’) and secondly, for friends who allow for that confusion by encouraging my ownership of the thinking process rather than offering unsolicited advice and premature conclusions.