A study out of Stanford University some twenty years ago examined why some doctors are sued more than others. We, the patients, cannot assess accurately their medical expertise. We look at the certificates on the wall, during the procedure we are often anesthetized, and on recovery, look to see how straight is the line of stitches. No, we evaluate doctors on their bedside manner. Doctors with good communication skills are sued less often than those without.

In December of 2013 the Center for Food Integrity argued that in an era when smart phones can take videos so easily, farmers need to run their operations as if someone is recording their activities. What, they asked, separates the ‘good actor’ from the ‘bad actor’ farmers and how does this relate to the level of trust that consumers have in their products?

If we substitute ‘beekeeper’ for ‘farmer,‘ there are two major consequences. First, as a beekeeper’s operation grows in size it starts to look to the consumer as ‘institutional’, and the more institutional it looks, the less the consumer believes he or she can trust the beekeeper. The larger the operation the more likely it is perceived as putting profit above public interest.

Secondly, the values held by the beekeeper are more important to the public than his or her technical competence. We tend to speak to the public and answer questions in scientific and technological terms but consumers are primarily concerned with the availability, affordability and safety of healthy foods, in this case honey or the crops that honey bees pollinate.

To address those values the beekeeper needs to have earned public trust and be transparent. Easier said than done, right? So the CFI polled 6000 people and discovered that ‘bad actors’ typically discounted public concerns, passed on the blame and were not consistent in their informational data. ‘Good actors,’ by comparison, focused on addressing perceived problems, did not hesitate to bring in other expertise and focused on larger issues like health and well being. Good actors, in other words, listened hard and addressed real concerns.

Good actors, or in our case good beekeepers, keep good records (which can be a valid source of their methodology if support is needed,) participate in honey bee related programs, have a good relationship with local expertise and accept responsibility when things don’t work out as they would like.

A report in Lancaster Farming, December 7, 2013, which is where I first read of this report, ends thus : “(Beekeepers) need to demonstrate and communicate an understanding of the ethical obligation to provide for the well being of (honey bees.) And they need to communicate that their commitment to doing what is right goes beyond their economic interests.”

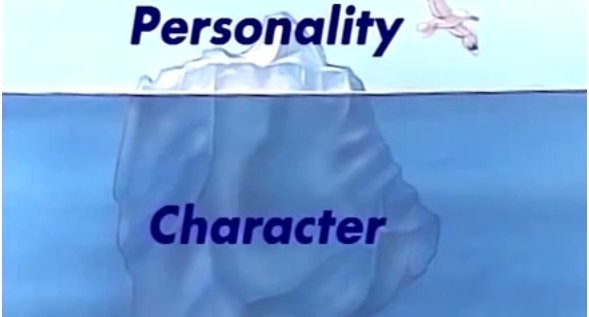

Clearly none of the above is limited to farming and beekeeping. The late Stephen Covey described the difference between personality and character in The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. The second half of the last century saw the promotion of the personality ethic, when the new genre of self-help books stressed appearance, technique and a positive mental attitude. Valuable as these are, they lack meaning unless they are based on primary principles of character such as integrity, humility, courage, patience and ‘the Golden Rule.’ Covey said we can get by using the personality ethic to help make favorable first impressions but these secondary traits have no prolonged worth in long-term relationships. “Eventually, if there is no integrity, the challenges of life will reveal one’s true character. As Emerson once said, ‘What you are shouts so loudly in my ears I cannot hear what you say.’ “

To illustrate the difference he asks that you imagine being in say New York, and using a map to find the Statue of Liberty.. You may have excellent map reading skills but they will be to no avail if your map is of Washington, DC. In other words you must have the right map (character, or primary skills) before the secondary skills (personality) can be effective. A pertinent example is the late Nelson Mandela, who exemplified a depth of character for which he initially suffered and eventually triumphed. As President Obama said at his memorial service, he represented “principles that need to be chiseled into law.” Mandela personified the difference between a statesman and a politician; we have too many of the latter and too few of the former.

I spend a lot of money at True Value, the local hardware store. I don’t begrudge it; I am known there by both face and name and feel more than just a customer. It’s an inviting, helpful environment and every visit feels like a win:win situation; I feel welcome, I get what I need in terms of both advice and materials, and they keep my business. It’s one of the many advantages of living in a small, semi-rural community.

True Value occasionally sends out gift certificates to its customers. Checking out of the store on a recent visit, I mentioned to Marion behind the counter that I had received such a certificate but had left it at home. She immediately gave me the gift (a first aid kit for the car) and said I could return the certificate on my next visit. When I returned the next day, certificate in hand, the response of the young lady at the till (it was Marion’s day off) was interesting. She was clearly surprised which led me to believe that based on previous experiences there had been no expectation that the request would be honored. For me there was no question that I would respond in any other way; the agreement had been based on mutual trust and respect, qualities that are too important to be taken for granted or abused.

A 2012 study at the University of Illinois suggested that bees have different personalities, with some showing a stronger willingness to seek adventure than others. The researchers found that thrill-seeking is not limited to humans and other vertebrates. The brains of those honeybees that were more likely than others to seek adventure exhibited distinct patterns of gene activity in molecular pathways known to be associated with thrill-seeking in humans. Rather than being a highly regimented colony of interchangeable workers taking on a few specific roles to serve their queen, it now seems that individual honeybees differ in their desire to perform particular tasks and these differences could be due to variability in bees’ personalities. This supports a 2011 study at Newcastle University that suggests honeybees exhibit pessimism, indicating that insects might have feelings.

An experienced beekeeper can learn much by simply listening to a colony – they communicate clearly and unambiguously. One evening in Alsace Erik Delfortrie was opening some hives for my benefit and after the third one he said it was time to close them up. “How do you know?” I asked. In response he held his hand to his ear. Erik is a good beekeeper and, like his bees, a good actor. He is also a man of character and one could sense it immediately on meeting him. Ultimately a contrived personality cannot hide character defaults. Thus we cherish the basic character traits of honey bees – their industry and work ethic, commitment to the greater society, patience, and relationship with the natural world, for instance – and accept the differences of personality that each colony displays.

There is a critical difference of course between honey bees and ourselves. The behavior of the former, as best we know, is essentially the result of their genetic makeup. Bees do not make conscious choices; rather they respond automatically to the chemical bouquets we call pheromones. We too have a genetic disposition but it is moderated by nurturing, first by others (normally our parents) and then by ourselves. Every day we make thousands of conscious choices, each one dictated by a moral value as expressed in our personality and character.

And that was the lesson of my visit to True Value. In an age that has come to expect no more than personality (saying the right thing is more important than doing the right thing) I had made a choice based on character (following words with action) and it felt good.