Sara George’s historical novel, The Beekeeper’s Pupil, is the story of the remarkable relationship between the blind naturalist, Francois Huber, and his manservant and ‘eyes’, Francois Brunens, as they investigate the behavior of the honeybee against the backdrop of the Scientific and French Revolutions.

The story is presented as the fictionalized diary of the latter from the date of his appointment in 1785 to his departure from the household nine years later. On October 10, 1789, the entry reads in part, “We feel as though we’re living in uncertain times, as though what has always seemed the natural order is beginning to turn upside down. The Paris mob dictating to the King of France. It would have seemed unthinkable even a week ago.”

In the study of Group Dynamics there is a concept called the Groan Zone. In essence it says that an essential part of the creative process is the ability to let go of preconceived notions and expected outcomes and to be truly open and available to the possibilities based on the questions asked and the data available. It is uncomfortable – one has to set aside one’s comfort zones and agendas – hence the term Groan Zone. It’s proponents argue that despite the discomfort it is important to stay present, to stay involved, until a new paradigm emerges from what feels like chaos.

It seems ironic, for example, that the turmoil of the late C18th in both American and France is now called ‘The Enlightenment.”

Today there is an argument that the world, rather than any one single country, is in a state of transition which is both a threat and an opportunity that rarely occurs. There is a sense that the global economic system is not working, the political system is no longer democratic or representative, society is dysfunctional and religious systems are honored more in word than in action. These systems worked well once upon a time but today they are corrupt and broken. We find witness in the Arab Spring, the economic plight in Greece, the rise of the extreme right wing in Europe, the increasing political divides in the US, the on-going turmoil in much of Africa, the drug wars in Mexico, the chaos in the Middle East …

A significant percentage of the population yearns for security, for a return to the perceived stability and comforts of the past, for the predictability of the known with an emphasis on what worked best in earlier times. I use the word ‘perceived’ because it is easy to romanticize both the past and the future.

Such yearnings are understandable and very human.

There are others who see this as an opportunity. They argue these systems worked before but times have changed and rather than try to resurrect them we need to let go of preconceived notions and expected outcomes and avail ourselves of new possibilities.

This too is an understandable and human condition.

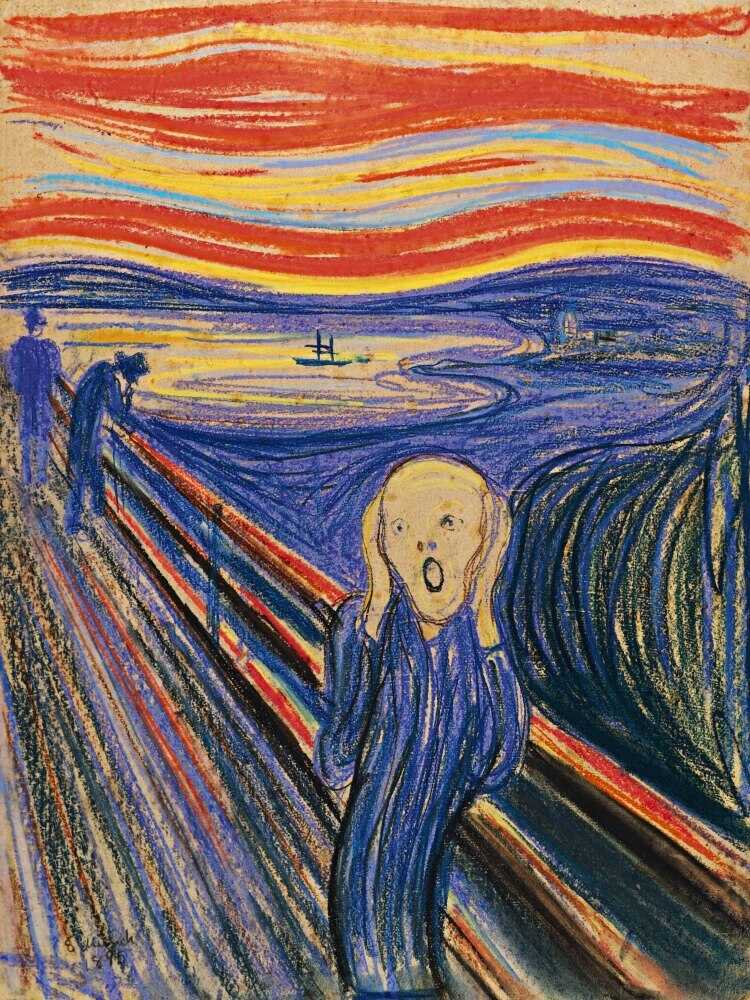

Perhaps we are in a global groan zone, the dichotomy and tension of which is uncomfortable but vitally important whatever the result. How felicitous that Edvard Munch’s painting, The Scream, which for me symbolizes the intense feelings and tensions that preceded the First World War, sold in 2012 for $120 million, until then the most ever paid for a single painting. (In October, 2017, after 19 minutes of dueling between five bidders. a disputed and much restored Leonardo da Vinci portrait, Salvator Mundi, sold for $450 million.)

Honey bees have a role to play as we navigate these tricky waters. Thomas Seeley defines a ‘smart swarm’ as “A group of individuals who respond to one another and to their environment in ways that give them power, as a group, to cope with uncertainty, complexity and change.” He is describing more than just honey bees. “It is from controlled messiness that the wisdom of the hive emerges” writes Peter Miller in his book, Smart Swarm, which includes fish, birds and ants together with honey bees.

With increased frequency bees are referred to as our ‘canaries in the coal mine.’ To counteract the lack of ventilation in early coal mines, miners would routinely bring a caged canary, a bird that is super sensitive to carbon monoxide, into new coal seams. As long as the bird kept singing the miners knew their air supply was safe. A dead canary signaled an immediate evacuation, which was too little too late for the poor bird but good for the men. The implication is that the current difficulties experienced by honey bees are symptomatic of an increasingly toxic environment. Unlike the miners, however, we cannot simply evacuate our environs as the bees die.

The bees also offer us solutions. In Honey Bee Democracy, Thomas Seeley draws lessons for effective group behavior from the way honey bees make decisions when swarming – decisions made under pressure that are vital to the survival of the colony – and if the bees are indeed our modern canary equivalents, decisions that might be vital for the future quality of life as we know it. For example, how would the current political debate in this country change if, like the bees, we chose to put our egos aside, check the accuracy of information for ourselves, utilize the power of positive feedback, value diversity in terms of effective decision making, debate respectfully in an atmosphere of open enquiry, and champion fresh ideas? What would change if these traits could be modeled in the public sphere and encouraged in our schools?

For environmentalist Bill McKibben, the solution lies in working with nature rather than against it. “Past a certain point, we can’t make nature conform to our industrial model. The collapse of beehives is a warning – and the cleverness of a few beekeepers in figuring out how to work with bees not as masters but as partners offers a clear-eyed kind of hope for many of our (ecological) dilemmas.”

Partnership rather than opposition, cooperation rather than competition, and above all a focus on the long term survival and health of the community, are qualities that we witness in the hive and which most of us practice at our beekeeper meetings. They might also be touchstones as we navigate through the global Groan Zone.