In the past sixty years there have been two significant publications related to learning, both which are mentioned elsewhere in these reflections. One is Howard Gardener’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences, published in 1983 as described previously.

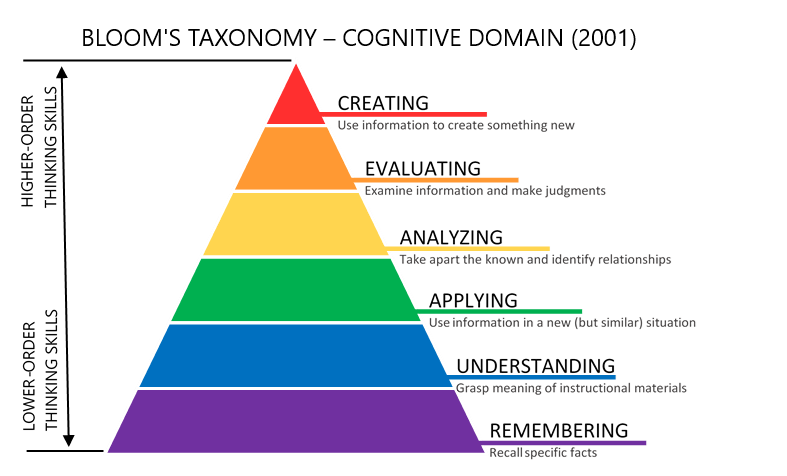

The second study is The Taxonomy of Learning Domains, published in 1956 by a committee chaired by Dr. Benjamin Bloom. The cognitive domain, which involves knowledge and the development of intellectual skills, consists of six categories normally presented in the form of a pyramid, with the more complex skills standing atop the more simple ones in that the first one must be mastered before the next one can take place.

Paraphrasing Bloom’s terminology, the first two levels (often referred to as lower order thinking skills) are a familiarity with and comprehension of the basic knowledge or data. The four upper levels relate to the ability to apply that information by means of analyzing a situation, blending and utilizing different options, evaluating the results and possibly creating something that is specifically relevant if not new.

Bloom’s Taxonomy is not to be confused with Maslow’s Hierarchy, the latter referring mainly, but not exclusively, to personal growth, although there are intriguing similarities between the two.

Our school systems, including colleges, are often primarily concerned with the lower order skills, not least because they can be easily and quickly measured in standardized tests. I have not yet seen a multiple choice test that measures higher order thinking skills, although they might exist. An acquaintance who is studying to be a nurse broke the radius bone in her right arm in two places. When I asked how she would cope with school (she is taking night classes) she replied that fortunately the professor hands out notes at the beginning of each class and the students have only to highlight those parts that will be on the test. No higher order thinking required.

Too often the unspoken game that students play in school is “What Does Teacher Want?” Work out what the teacher expects, give it back to him/her, and a good grade is assured. The skills are lower level (understand the data) and validation is external; we rely on others to tell us what is right, what is good, what is important.

A conversation with Jim Bobb, a doyen of Pennsylvania beekeepers, clarified that Bloom’s Taxonomy has relevance for beekeeping. Yes, it is important that one knows the basic data and understands it. No meaningful analysis can take place without that knowledge and a major responsibility of any beekeeper is to be well informed. But the only way to learn how to apply knowledge is to get one’s hands dirty, to get into a hive as often as possible and to make decisions that are particular to that colony based on a combination of the evidence on the frames and the theory from the literature. Randy Oliver, in his frequent presentations, concurs.

There is no single recipe for beekeeping. A good spring management class or winter preparation article is not a prescription so much as a set of principles based on honey bee biology and behavior that offer choices. Increasingly, when asked “What do I do now with my hive?” my response is not to be directive (tempting as it is) but to describe possible courses of action based on the particular state of the bees.

Ultimately each successful beekeeper develops a particular style of management that is creative and unique to their objectives, their location and their bees. That’s the higher order thinking skills at work. Anything less is like trying to understand Mozart as no more than a series of sound waves caused by the disturbance of molecules in the atmosphere.