The following sentence is patently obvious yet needs to be written nonetheless. At no time in the last 10 000 years has humankind produced, used, and carelessly discarded such a ruthless combination of chemical and toxic substances as the present.

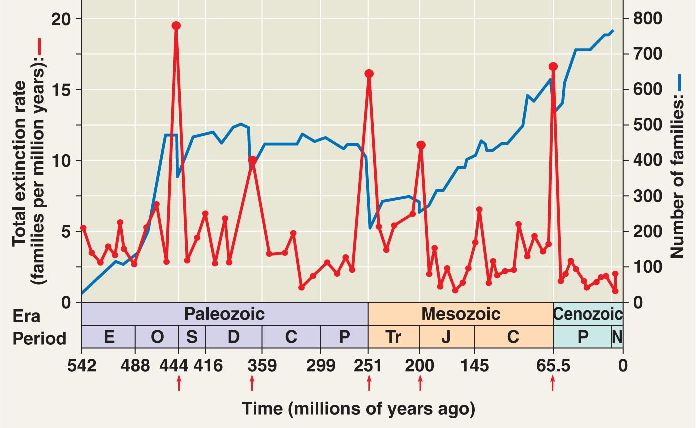

It’s tempting to think that the last time the environment was ruthlessly toxic was after an asteroid collided with the earth some 65 million years ago, which led to what is referred to as the Fifth Extinction and which included an end to the age of the dinosaurs. And yes, extinction is a natural feature of evolution because for some species to succeed, others must fail. Since life began, an estimated 99% of the earth’s species have disappeared and, on at least five occasions, huge numbers have died out in a relatively short time. But despite such catastrophes the total number of living species has, until recently, followed a generally upward trend.

Today the extinction rate is increasing as a result of human interference in natural ecosystems combined with human behaviors which are unquestioned and unconscious. We are steadily encroaching on the habitat of millions of species while fundamentally altering the environment, a trend eloquently described by Fulbright scholar and writer for the New Yorker, Elizabeth Kolbert, in The Sixth Extinction : An Unnatural History.

This decline will continue because evolution generates new species far more slowly than the current rate of extinction. More than 320 terrestrial vertebrates have gone extinct since 1500, according to researchers at Stanford University. Surviving species have declined by about 25%, particularly devastating the ranks of large animals like elephants, rhinoceroses and polar bears. The U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report of 2007 predicted that an increase of 3.5 degrees celsius, which is within the range of scientific forecasts for 2100, could wipe out 40 to 70 % of the currently known species.

According to the Israeli scientist, Yinon Bar-On, since the rise of human civilization 10 000 years ago, wild animal biomass has fallen by 83 per cent. The surviving wild mammals now comprise a meagre 4 per cent of all mammalian biomass, with our livestock comprising 60 per cent and humans the remaining 36 per cent. In other words, our domestic cattle, hogs and sheep outweigh 15 times the 5 000 feral mammalian species, and the collective mass of humanity city is is 9 times heavier.

To add to that, 70 per cent of global bird biomass is now comprised of domestic poultry.

The reasons are complex and range from our arrogance, our unjustified sense of superiority, our supposed divine right to ‘dominion over the earth,’ our unbounded belief that somehow we can do no permanent harm, an economic system that measures everything primarily in terms of money, and an unbridled confidence in the righteousness of unrestricted science. Consider that everything we eat, drink, wear and drive is infused with a complicated variety of chemicals with impossible sounding names, like polysalinate 80 (in a jar of dill pickles,) calcium disodinate EDTA (in mayonnaise,) nonylphenol ethoxylates and phthalates (in shirts,) acesulfame potassium in sodas, and bisphenol A (in plastic bottles and the plastic in our vehicles.) Do we really know what these are, what their long term consequences are, how they interact with elements in our bodies and our environment? A painful lesson from the bees is that the interaction between chemicals in a hive can increase their toxicity as much as one thousand times. They can also cancel one another out.

And then there is the power of advertising, the purpose of which is to make us feel dissatisfied and inadequate, that somehow if what we have is not faster, bigger, glossier or newer, we are in some way inferior and deficient. Many of the best minds in the country are paid a lot of money to make us feel that way and to persuade us to buy our way to fulfillment without consideration for the larger consequences. It is capitalism without morality, a free market without an environmental conscience.

A news segment recently on back-to-school shopping stressed that it all starts with the right pair of shoes, that the school wardrobe has to be built from the ground up, and emphasized the pressure many parents undergo from children who believe they need brazen sneakers that their parents cannot afford. Shoes? Really?

Personal disclosure – as described earlier, I do not have a smart phone, nor do I want one. I have lived my life relatively successfully without having immediate access to reams of data nor with allowing people who would never drop by unannounced to have unlimited access to my time and to expect immediate responses. Nor do I have a GPS – I actually enjoy reading maps, making choices as to my routes and learning about the countryside as I go. Yes, I’m a curmudgeon. The above are conscious choices, in part a deliberate resistance to the bombardment of advertisers and in part a personal preference for voluntary simplicity. I am satisfied as I am and with what I have, thank you, and increased materialism will not change that. I must be hell to buy for on birthdays!

This is what I understand by the frequent reference to honey bees as our canaries in the coal mine. Bees are super-sensitive to an increasingly complex, toxic environment in which we all exist, in which we all live, drink and breath, without much in the way of alternatives.

Is this depressing? I don’t think so. Recently I was given a DVD called Happy (someone must have felt I really needed it!) which travels from the swamps of Louisiana to the slums of Kolkata (Calcutta) in search of what really makes people happy. The conclusions include that happiness is a skill, like golf, that can be honed with practice, that it means being authentic to oneself, that relationships with friends and family are important, that it comes from seeking new experiences and doing things that are meaningful. Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu would describe this as joy rather than happiness, in that it is internally induced rather than determined by external events (more of that later) but it is the emphasis on meaningfulness that struck a chord. Keeping bees, like planting trees or shopping critically, is a meaningful act. It is something positive we can do in the face of large challenges, and feeling that one is a conscious part of the solution rather than an unconscious part of the problem is both satisfying and rewarding if not joyful.