In the February, 2014, issue of Harper’s Magazine entitled Tunnel Vision : Will the Air Force Kill its Most Effective Weapon? an Air Force colonel describes a conflict in Afghanistan involving predator drones. “If you want to know what the world looks like from a drone feed, walk around for a day with one eye closed and the other looking through a soda straw. It gives you a pretty narrow view of the world.” Experienced A-10 pilots use the soda straw analogy in describing the video images from their targeting pods. “You can find people with the targeting pod,” said one such pilot, “but when it’s zoomed in I’m looking at a single house, not anything else… If you’re looking only through the soda straw you don’t know everything else that’s going on around it.”

Once upon a time our learning started with the narrow and became increasingly broad – the typical Classical education of the nineteenth century, for example. Today the tendency is to start with the generic after which we become increasingly focused on minutiae.

New beekeepers begin with a narrow focus, understandably and rightly so. They focus on basic management skills, ask rudimentary questions, learn the terminology. There is normally a romantic reason for getting involved – doing one’s part to save the bees, wanting an individual source of honey, wanting to increase pollination in one’s garden …Nothing wrong with any of those motivations.

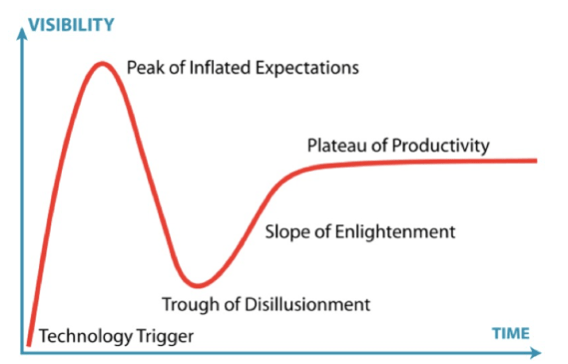

And then typically there is a major obstacle, a disillusionment. The bees swarm, the queen is poorly mated and the bees wither, the colony does not survive the winter, varroa mites and wax moths take over the hive. In the face of what Gartner and Hype call ‘the trough of disillusionment’ many new beekeepers, perhaps as many as half, decide not to continue.

Those who those who persist do so partly because they had realistic expectations and knew in advance that all beekeepers, no matter how good, lose colonies, heart wrenching as such l oss always is, and partly because they have a good

mentor who can encourage them despite the disappointment. These survivors enter the ‘slope of enlightenment’ where gradually they open themselves to the complexity of this fascinating hobby, and with that enhanced, deepened and broadened awareness comes the real fascination and wonder that the intricate world of honey bees can provoke. This gradual slope leads eventually to the ‘plateau of productivity’ which is when the most profound learning occurs, when meaningful interpretations and predictions of colony behavior can be discerned, and when the beekeeper interacts with the larger environment in which the bees exist.

There is no shortcut. It’s a hands-on learning process with trial and error as a demanding teacher.

Successful beekeeping, as with so many other things in life, is the gradual process of moving from simplicity to complexity. I suspect that effective beekeeping classes and good mentoring follow the same pattern. Yet ultimately it is up to the individual student to embrace complexity, to open himself or herself to the variety and apparent confusion of the different worlds behind the book covers, and to resist the temptation to accept the quick and easy solution. “The test of a first-rate intelligence,’ said F. Scott Fitzgerald, “is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

A colony can be viewed in the same way. At one level the life progress of a worker bee is relatively simple – her cycle from egg to maturity and the tasks she completes in a hive are easy to comprehend. But when one begins to ask what stimulates her to change activities from say collecting nectar to collecting water, or how she responds to the pheromones emanating from a larva in an uncapped cell, it gets a little more complex, and even more so when one looks at the colony as an entity with the numerous individual interactions that make up the superorganism and the complex social and behavioral organization that enables the effective use of available material and energy.

For me, the greater the complexity the greater the sense of wonder, even more so as I see honey bees as metaphors and teachers for the Gordian Knot that is our current world. The constant challenge, whether talking over the phone to a nu-bee or addressing queries at an open forum, is how to convey both the necessary simplicity and the amazement of the complex without confusing or dampening the enthusiasm of the listener. Typically the decision as to whether to move to more complex answers is determined by the questions from the audience, which disclose their level of interest and comprehension and determine whether the rejoinder invites them to open a book of self-discovery or is a more direct googlesque response.

For the first 25 years of my teaching career a student assignment came with the assumption that it would involve time spent in the school library; indeed I would work closely with the librarian in preparing the assignment. In more recent years, with a laptop or even a smart phone, students can comfortably complete an assignment without having to leave their dorm rooms. And when I get to visit the college library today the majority of the students are sitting at computer terminals rather than looking at books on the shelves. (Those not at the computer are asleep on chairs in the corners!)

Those books on the shelves, like bee hives, can appear at a casual glance to have a ‘sameness’; one has to look behind the covers to realize how different each one is.

My concern is that as one searches for a book in a library, as one pages through the index or flips through the chapters, knowledge is found in a larger context. A Google search, by comparison, takes one straight to the requested page or paragraph; it’s a direct but narrow search. The student is taken to the precise phrase or word he or she is searching for without any reference to background or theme or context. The result, all too often, is a good final paper with minimal understanding of the bigger picture.

This came to mind reading an article in the February, 2014, issue of Harper’s Magazine entitled Tunnel Vision : Will the Air Force Kill its Most Effective Weapon? Describing a conflict in Afghanistan involving predator drones, an Air Force colonel is quoted as saying, “If you want to know what the world looks like from a drone feed, walk around for a day with one eye closed and the other looking through a soda straw. It gives you a pretty narrow view of the world.” Experienced A-10 pilots use the soda straw analogy in describing the video images from their targeting pods. “You can find people with the targeting pod,” said one such pilot, “but when it’s zoomed in I’m looking at a single house, not anything else… If you’re looking only through the soda straw you don’t know everything else that’s going on around it.”

Once upon a time our learning started with the narrow and became increasingly broad – the typical Classical education of the nineteenth century, for example. Today the tendency is to start with the generic after which we become increasingly focused on minutiae.

New beekeepers begin with a narrow focus, understandably and rightly so. They focus on basic management skills, ask rudimentary questions, learn the terminology. There is normally a romantic reason for getting involved – doing one’s part to save the bees, wanting an individual source of honey, wanting to increase pollination in one’s garden …Nothing wrong with any of those motivations.

And then typically there is a major obstacle, a disillusionment. The bees swarm, the queen is poorly mated and the bees wither, the colony does not survive the winter, varroa mites and wax moths take over the hive. In the face of what Gartner and Hype call ‘the trough of disillusionment’ many new beekeepers, perhaps as many as half, decide not to continue.

Those who those who persist do so partly because they had realistic expectations and knew in advance that all beekeepers, no matter how good, lose colonies, heart wrenching as such l oss always is, and partly because they have a good mentor who can encourage them despite the disappointment. These survivors enter the ‘slope of enlightenment’ where gradually they open themselves to the complexity of this fascinating hobby, and with that enhanced, deepened and broadened awareness comes the real fascination and wonder that the intricate world of honey bees can provoke. This gradual slope leads eventually to the ‘plateau of productivity’ which is when the most profound learning occurs, when meaningful interpretations and predictions of colony behavior can be discerned, and when the beekeeper interacts with the larger environment in which the bees exist.

There is no shortcut. It’s a hands-on learning process with trial and error as a demanding teacher.

Successful beekeeping, as with so many other things in life, is the gradual process of moving from simplicity to complexity. I suspect that effective beekeeping classes and good mentoring follow the same pattern. Yet ultimately it is up to the individual student to embrace complexity, to open himself or herself to the variety and apparent confusion of the different worlds behind the book covers, and to resist the temptation to accept the quick and easy solution. “The test of a first-rate intelligence,’ said F. Scott Fitzgerald, “is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

A colony can be viewed in the same way. At one level the life progress of a worker bee is relatively simple – her cycle from egg to maturity and the tasks she completes in a hive are easy to comprehend. But when one begins to ask what stimulates her to change activities from say collecting nectar to collecting water, or how she responds to the pheromones emanating from a larva in an uncapped cell, it gets a little more complex, and even more so when one looks at the colony as an entity with the numerous individual interactions that make up the superorganism and the complex social and behavioral organization that enables the effective use of available material and energy.

For me, the greater the complexity the greater the sense of wonder, even more so as I see honey bees as metaphors and teachers for the Gordian Knot that is our current world. The constant challenge, whether talking over the phone to a nu-bee or addressing queries at an open forum, is how to convey both the necessary simplicity and the amazement of the complex without confusing or dampening the enthusiasm of the listener. Typically the decision as to whether to move to more complex answers is determined by the questions from the audience, which disclose their level of interest and comprehension and determine whether the rejoinder invites them to open a book of self-discovery or is a more direct googlesque response.